November 12, 2019

Indian Novels Collective

Tags

BOOK EXCERPT

Indian Writing: History and Perspectives

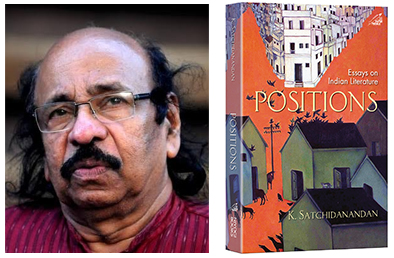

An eminent poet, critic, translator, playwright and travel-writer, K. Satchidanandan is often regarded as a torch-bearer of the socio-cultural revolution that redefined Malayalam literature. His first collection of poems, ‘Anchu Sooryan’ (Five Suns) came out in 1971 and since then he has published more than 20 collections of poetry. He has also authored an equal number of collections of essays on literature, philosophy and social issues, two plays, four books of travelogues and a memoir in Malayalam, besides four books on comparative Indian literature in English. He has won 51 awards including the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award and National Sahitya Akademi Award, Knighthood by the Govt of Italy, Dante Medal by Dante Institute, Ravenna, International Poetry for Peace Award by the government of UAE, and Indo-Polish Friendship Medal by the Govt of Poland.

An eminent poet, critic, translator, playwright and travel-writer, K. Satchidanandan is often regarded as a torch-bearer of the socio-cultural revolution that redefined Malayalam literature. His first collection of poems, ‘Anchu Sooryan’ (Five Suns) came out in 1971 and since then he has published more than 20 collections of poetry. He has also authored an equal number of collections of essays on literature, philosophy and social issues, two plays, four books of travelogues and a memoir in Malayalam, besides four books on comparative Indian literature in English. He has won 51 awards including the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award and National Sahitya Akademi Award, Knighthood by the Govt of Italy, Dante Medal by Dante Institute, Ravenna, International Poetry for Peace Award by the government of UAE, and Indo-Polish Friendship Medal by the Govt of Poland.

His latest work, ‘Positions: Essays on Indian Literature’ features a careful selection from his essays on Indian literature, written over the past 25 years. The book contains essays that look for paradigms based on Indian textual practices and reading traditions, while also drawing freely on Indian and western critical concepts and close readings of certain texts. The first part of the book discusses questions on the idea of Indian literature, the poetics of Bhakti, the concept of the ‘modern’, the location of English writing in India, the conflicting ideas of India, projected especially by the subaltern literary movements and the issues of literary criticism and translation. The second part of the book discusses the work of individual authors including Sarala Das, Mirza Ghalib, Kabir, Rabindranath Tagore, Saratchandra Chatterjee, Sarojini Naidu, Kedarnath Singh, A.K. Ramanujan and Kamala Das.

‘Positions’ contribute to the growing, yet insufficient, corpus of literary studies in India.

Here’s an excerpt from the book:

THE PLURAL AND THE SINGULAR

The Making of Indian Literature

Whenever I think of Indian literature, a story retold by A.K. Ramanujan comes to mind: Hanuman reaches the netherworld in search of Rama’s ring that had disappeared through a hole. The King of Spirits in the netherworld tells Hanuman that there have been so many Ramas over the ages; whenever one incarnation nears its end, Rama’s ring falls down. The King shows Hanuman a whole platter with thousands of rings, all of them Rama’s, and asks him to pick out his Rama’s ring. He tells this devotee from earth that his Rama too has entered the river Sarayu by now, after crowninghis sons, Lava and Kusha. Many Ramas also mean many Ramayanas and we have hundreds of them in oral, written, painted, carved and performed versions. If this is true of a single seminal Indian work, one needs only to imagine the diversity of the whole of Indian literature recited, narrated and written in scores of languages. No wonder, one of the fundamental questions in any discussion of Indian literature has been whether to speak of Indian literature in singular or plural. With 184 mother tongues (as per Census, 1991; it was 179 in George Grierson’s Linguistic Survey of India, along with 544 dialects, and 1,652 in 1961), 22 of which are in the Eighth schedule of the Indian Constitution; 25 writing systems, 14 of them major, with scores of oral literary traditions and several traditions of written literature, most of them at least a millennium old, the diversity of India’s literary landscape can match only the complexity of its linguistic map. Probably it was this challenging complexity that had forced an astute critic like Nihar Ranjan Ray to conclude that there cannot be a single Indian literature, as there is no single language that can be termed ‘Indian’.

Excerpt published with the permission of the publisher: Niyogi Books Pvt Limited.