October 10, 2020

Sohini Banerjee & Mansi Dhanraj Shetty

Listicle

Explore mental health through these seven reads in Indian literature

The ongoing pandemic has wrought a debilitating impact on the collective mental health of the global community. According to a survey carried out among health professionals by The Bengaluru-based Suicide Prevention Foundation observed that nearly 65% therapists observed an increase in self-harm and suicide ideation or death wish amongst those who sought therapy, since the pandemic hit. This alarming statistic of soaring mental health cases, due to a combination of factors like forced isolation, fear of the virus, financial insecurity, domestic violence and rising anxiety, have further aggravated the unprecedented humanitarian crisis. Now more than ever, it is imperative that we fight the stigma and backlash around mental illness, which has long been a cultural taboo in the Indian social context, owing to widespread ignorance, misinformation and lack of health care resources. Literature, as a domain, ensures increased awareness about mental health issues and challenges the problematic stereotypes which relegate them to the closet. It accomplishes this by providing a peek into the many-shaded contradictions, ambiguities and vulnerabilities associated with mental health crises, facilitating catharsis, healing and emotional empowerment.

Indian literature’s nuanced exploration of mental health began much before it was integrated into our common vocabulary. Jayakanthan’s ‘Rishi Moolam’ and Shanta Gokhale’s ‘Rita Welinkar’ or ‘Avinash’ are striking examples of the same. This World Mental Health Day, we bring to you a diverse selection from the repository of Indian literary canon which reflect and address mental health. Although not an exhaustive list, these books enlighten us on how there is no one sanctioned way to engage with subterranean depths of the human mind.

Rita Welinkar by Shanta Gokhale

Rita Welinkar by Shanta Gokhale

Marathi

First Published 1990, translated into English by the writer herself in 1995

Outside, the palm trees wail, with the wild monsoon wind in their hair. In her hospital bed, Rita lies still, her eyes tuned to the wind. Recovering from her breakdown, she sifts through seasons full of memories—of her self-absorbed, critical parents; her demanding role as family breadwinner from the age of eighteen; her secret for an understanding of the events that brought her to the breaking-point. This well-structured novel helps readers understand what leads to Rita’s nervous breakdown and how important it is to recognise and address it as it is. Translated by Shanta Gokhale herself from the Marathi original, ‘Rita Welinkar’ won her much critical acclaim and the VS Khandekar Award from the Maharashtra government.

Rishi Moolam by Jayakanthan

Rishi Moolam by Jayakanthan

Tamil

First Published 1969

In his preface, Jayakanthan writes, ‘an individual devoid of a healthy orientation towards the man-woman relationship cannot be considered a properly developed person.’ In ‘Rishi Moolam’ Rajaraman, the protagonist, suffers from a psychosis about his sexuality. Not being able to forgive himself for thinking and acting in an unscrupulous way with his mother-like figure, the story captures his inner turmoil, self-denial and self-perception. The success of Jayakanthan lies in evoking in the reader a profound empathy with the tragically ‘deviant’ character who is a victim of a psychological malady arising from his suppressed libido and Oedpius complex rather than condemning him to moral policing.

Swadesh Deepak by Maine Mandu Nahin Dekha

Swadesh Deepak by Maine Mandu Nahin Dekha

Hindi

First Published in 2003

Swadesh Deepak, Hindi novelist, Sahitya Akademi winning playwright, short-story writer is remembered for his memoir ‘Maine Mandu Nahin Dekha’, an account of his seven-year battle with bipolar disorder. First serialised in the Hindi monthly, ‘Kathadesh’, the book accounts for shifts between time and space showing the reader the fragmented, collage-like quality of Deepak’s life as he dealt with his inner demons. The searing 331-page book is also being translated into English by Jerry Pinto.

Raat ka Reporter by Nirmal Verma

Raat ka Reporter by Nirmal Verma

Hindi

First published in 1989

Set during the Emergency (1975-77), Nirmal Verma’s ‘Raat ka Reporter’ addresses the theme of totalitarianism, oppression and violence that marked those 21 months. The protagonist Rishi is a journalist who gets warned about government surveillance and the possibility of his arrest at any time. By offering a lens into Rishi’s sudden realisation of impending custodial torture accompanied by his anxiety inducing self-reflexivity being targeted as the ‘enemy’ of the state—‘Raat ka Reporter’ lays bare the pervasive climate of state-manufactured paranoia through a psychological analysis of a fear-stricken chapter in Rishi’s life.

Herbert by Nabarun Bhattacharya

Herbert by Nabarun Bhattacharya

Bengali

First published in 1994

Set in a corner of old Calcutta in May 1992, when communism was collapsing all around, Nabarun Bhattacharya’s Sahitya Akademi winning novel ‘Herbert’ introduces us to the titular character Herbert Sarkar, sole proprietor of a company that delivers messages from the dead. The ‘scathingly satiric and yet deeply tender’ portrayal of a doomed young man through a mosaic of manic and immersive episodes, also holds a mirror to the city struggling to resist the same forces as him, that prove to be entirely beyond their control.

Avinash by Shanta Gokhale

Avinash by Shanta Gokhale

Marathi

First published in 1988

Unfolding at a relentless pace over a tight span of twenty-four hours, Shanta Gokhale’s Marathi play ‘Avinash’ is an intense family drama in which the tensions between various members of a middle-class family over the mental health of the eldest son escalates to a tragic climax. Talking about the text, Shanta Gokhale mentioned, ‘A character in my 1988 play ‘Avinash’ says the depression his older brother suffers from may not be the result entirely of some inborn psychological tic. Its roots might also lie in economics, in the social structure and the political system.’

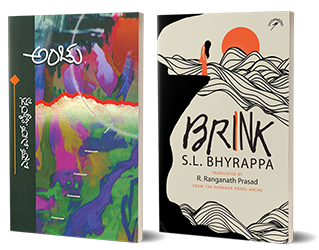

Brink by SL Bhyrappa

Brink by SL Bhyrappa

Kannada

First Published in 1990

SL Bhyrappa’s epic Kannada novel ‘Anchu’ or ‘Brink’ portrays the sensitive relationship between Somasekhar—a widower and caregiver, and Amrita—an estranged woman with suicidal tendencies. An important and timely book — ‘Brink’ raises the question of mental health awareness by addressing depression from the point of view of the person suffering as well as the caregiver and meditates on the moral, philosophical and physical aspect of love between a man and a woman.