Non Fiction: Manto Unvarnished

If asked to describe Saadat Hasan Manto in one word, this reviewer would unhesitatingly call him an enigma. Strange as it may seem, Manto, arguably the greatest short story writer in Urdu, failed in Urdu in his high school exams. What is no less surprising is that, incurable alcoholic that he was — he asked for whiskey while being driven in an ambulance to the hospital on his fatal journey and was obliged by his family members — he always wrote ‘786’, the numerical symbol of Bismillah ir Rahman nir Raheem, at the top of his writings, be they for broadcasting, publishing or films.

If asked to describe Saadat Hasan Manto in one word, this reviewer would unhesitatingly call him an enigma. Strange as it may seem, Manto, arguably the greatest short story writer in Urdu, failed in Urdu in his high school exams. What is no less surprising is that, incurable alcoholic that he was — he asked for whiskey while being driven in an ambulance to the hospital on his fatal journey and was obliged by his family members — he always wrote ‘786’, the numerical symbol of Bismillah ir Rahman nir Raheem, at the top of his writings, be they for broadcasting, publishing or films.

‘Fraud’ was his favourite word. He called many people — including his own self — a ‘fraud’, but as his childhood friend and biographer Abu Saeed Qureshi says, “He was a very transparent person and there appeared no gap between his internal and external selves.”

Manto Saheb: Friends and Enemies of the Great Maverick, featuring translations of articles by fellow writers, publishers and two close relatives on the enigmatic personality is, by and large, quite absorbing.

The first piece is by Saadat Hasan, the ‘twin’ of Manto the writer, who predicts — and quite rightly so — that the man would die but the writer would live on. But then that is applicable to all distinguished men of letters, be they William Shakespeare, Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib or Rabindranath Tagore.

One feels strongly that the finest piece on Manto should have been by his devoted, and often deceived, wife, Safia. He may have remained in love with her, but she was the one who suffered endlessly on his account. Every contributor to the volume under review has nothing but words of praise for the lady.

Writes their second daughter, Nuzhat: “My mother’s experience of life as a writer’s wife was far from pleasant. She never accepted Manto saheb’s habit of drinking excessively. And to top it all, he gave away money without hesitation … My mother used to often complain to him about his habit of frittering away money, especially when there was not enough to run the house.”

Nuzhat further reveals, “Ammi jaan used to be the first reader of father’s stories. She told us about our father’s exceptional talent. There were times when he would verbally dictate three different stories to three different people.”

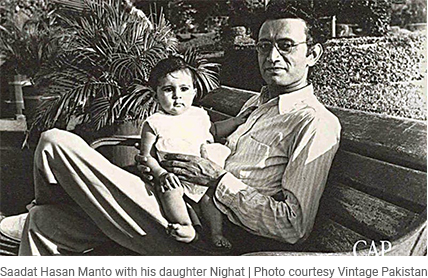

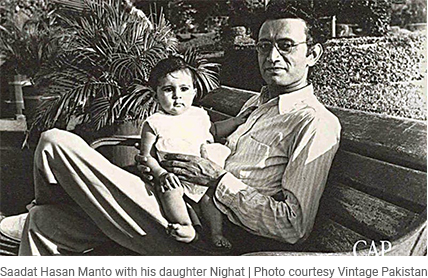

The biggest tragedy in Manto’s life is recalled by his friend Krishan Chander, another well-known fiction writer. It was the death of his eldest child, a year and a half old son. Writes Chander: “The armour of cynicism that he had built up all around himself was smashed to smithereens.” According to Manto’s eldest daughter Nighat, the loss affected her father so much that he was transformed from a social drinker to an irreversible alcoholic.

The biggest tragedy in Manto’s life is recalled by his friend Krishan Chander, another well-known fiction writer. It was the death of his eldest child, a year and a half old son. Writes Chander: “The armour of cynicism that he had built up all around himself was smashed to smithereens.” According to Manto’s eldest daughter Nighat, the loss affected her father so much that he was transformed from a social drinker to an irreversible alcoholic.

The longest piece in the book is by Urdu/Hindi writer Upendranath Ashk and is rightly titled ‘Manto, My Enemy’. While admitting that Manto had an inflated ego, one cannot ignore the fact that Ashk — a less accomplished writer — liked to provoke him. Once they even exchanged blows. Ashk was Manto’s contemporary at All India Radio (AIR), Delhi, and later at Filmistan Studios in Bombay [Mumbai]. Their skirmishes were a source of amusement to those present in the rooms. Not surprisingly, Ashk and his wife were admirers of “Safia bhaabi.”

When Manto got Ashk invited to join Filmistan, he hosted Ashk in his Bombay flat for a week. A fact that Ashk ungrudgingly acknowledges is that, whether at home or outside, Manto was invariably dressed in spotless and well-ironed clothes. Manto liked to dress in a lounge suit and matching necktie as much as he enjoyed sporting kurta-pyjamas, with or without covering himself with a sherwani.

His papers were well-stacked and his books properly shelved. Everything was placed in great order in the room of a person who otherwise led a disordered life.

Back to Ashk, his judgement that “Manto didn’t seem to realise that the strongest adversaries of humans are humans themselves,” is far from the truth. Manto’s stories built around Partition are about killers, rapists and their victims. Likewise, in his tales of pimps and prostitutes, he mentions in no uncertain words that young girls are kidnapped or enticed to enter into the flesh trade.

Poet and critic Ali Sardar Jafri criticises Manto for writing “obscene stories”, but also compliments him for his ability to narrate a story effectively. Jafri eulogises Manto for writing such exceptional stories as ‘Naya Qanoon’, ‘Tarraqqi Pasand’, ‘Mootri’, ‘Khol Do’ and ‘Toba Tek Singh’, but he joins Sajjad Zaheer in condemning such “painful but irrelevant” stories as ‘Boo’ and ‘Hatak’. Jafri, however, concedes that, “From the perspective of art, Manto was unique and unparalleled. No other writer had the ability to create the impact that Manto could with the simplicity, dexterity and perspicacity of his language.” Jafri is also all praise for Manto’s “sharp and astute” characterisation and “well structured” plots.

Perhaps the most readable of all the pieces in the book is ‘My Friend, My Foe’ by Ismat Chughtai, herself a bold writer of fiction. Manto was a blunt conversationalist and Chughtai did not believe in niceties either, so when she goes to see Manto for the first time, she decides to “pay him back in the same coin.” The two start arguing with all their might. When he addresses her as ‘sister’, she protests. “If you don’t like to hear the word then I will continue you to call you ‘Ismat behen’” comes the provocative reply.

Writes Chughtai, “If Manto and I decided to meet for five minutes, the programme inevitably stretched out to five hours.” The exchange of fireworks is not to the liking of Safia and Shahid Lateef, Chughtai’s spouse.

Manto and Chughtai have to go all the way from Bombay to Lahore where the local government has filed a case against them for what they called ‘obscene writings’. Chughtai is under fire for writing one of her most popular short stories, ‘Lihaaf’, which has veiled references to lesbianism. The two writers have a whale of a time interacting with Lahore-based Urdu writers.

They lose touch when Manto migrates to Pakistan. Manto is nostalgic about Bombay and, when Urdu poet Naresh Kumar Shad visits from India, he finds Manto remembering the people and the streets of the city he had left behind, quite passionately.

Another noteworthy piece is by Mehdi Ali Siddiqui, a judge in an obscenity case filed against Manto for his controversial story ‘Upar, Neechay Aur Darmiyaan’. The accused is restless. He wants the judge to give his judgement soon. Siddiqui is, luckily, an avid fan of Manto and believes that after the death of Premchand, Manto is the greatest Urdu writer. A token fine of Rs 25 is announced, which is duly paid by one of the writer’s guarantors.

Manto and his friends later go to the judge’s room and invite him to meet the writer at the centrally located Zelin’s Coffee House, where the two strike up a friendship. Manto insists that the story is based on truth. Shortly before his death, Manto includes the story in his new collection, a collection he titles ‘Upar, Neechay Aur Darmiyaan’ and dedicates it to Siddiqui.

Noted writer and editor of the literary magazine Saqi, Shahid Ahmed Dehlvi makes a relevant point when he says, “Everybody used to be astonished by Manto’s pace, and what was even more extraordinary was that everything he wrote would be precise and accurate, leaving absolutely no scope to tinker around with even a little.”

Mohammad Tufail, editor and publisher of the reputed literary journal Naqoosh, claims to have come to Manto’s rescue more than once. Manto wants Tufail to bring out a special issue on him and says that he will contribute his own elegy. But Tufail is late; he tries to make up by writing a letter from Manto — now settled in the other world — in Manto’s style and publishing it in the special edition of Naqoosh along with several writers who knew the man who kicked the bucket at the young age of 42.

A piece by Balwant Gargi, a novelist and playwright who wrote in Punjabi, makes for interesting reading too. Gargi narrates an incident dating back to the time when both he and Manto worked at AIR. A programme scheduled on a certain day is in jeopardy because the writer has not sent the script. Gargi and other colleagues of Manto at the Delhi station know that he could suitably fill the gap. On their insistence, Manto writes a play called Intezaar and Gargi maintains that it ranks among the best plays broadcast by AIR.

Not much has been lost in the translations of Manto Saheb: Friends and Enemies of the Great Maverick, but what is irksome is poor proofreading. The names of eminent people are misspelled. Can anyone be forgiven for writing ‘Jinha’ instead of ‘Jinnah’? Gujrat, the city in central Punjab, is spelled Gujarat (which is how the name of Narendra Modi’s state is written). ‘Martial law’ is written as ‘Marshall law’. The perfectionist that Manto was, he would turn in his grave if he were to see the copy of this otherwise useful book for those who can’t read the script in which the pieces were originally penned.

The reviewer is a senior journalist and author of four books, including Tales of Two Cities

Manto Saheb: Friends and Enemies of the Great Maverick

Translated by Vibha S. Chauhan and Khalid Alvi

Speaking Tiger, India

ISBN: 978-9388070256

287pp.

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, October 20th, 2019

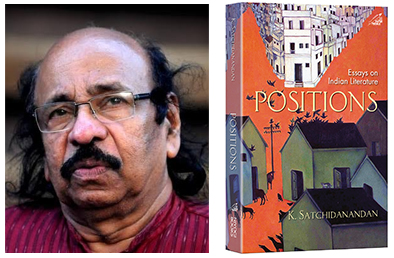

An eminent poet, critic, translator, playwright and travel-writer, K. Satchidanandan is often regarded as a torch-bearer of the socio-cultural revolution that redefined Malayalam literature. His first collection of poems, ‘Anchu Sooryan’ (Five Suns) came out in 1971 and since then he has published more than 20 collections of poetry. He has also authored an equal number of collections of essays on literature, philosophy and social issues, two plays, four books of travelogues and a memoir in Malayalam, besides four books on comparative Indian literature in English. He has won 51 awards including the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award and National Sahitya Akademi Award, Knighthood by the Govt of Italy, Dante Medal by Dante Institute, Ravenna, International Poetry for Peace Award by the government of UAE, and Indo-Polish Friendship Medal by the Govt of Poland.

An eminent poet, critic, translator, playwright and travel-writer, K. Satchidanandan is often regarded as a torch-bearer of the socio-cultural revolution that redefined Malayalam literature. His first collection of poems, ‘Anchu Sooryan’ (Five Suns) came out in 1971 and since then he has published more than 20 collections of poetry. He has also authored an equal number of collections of essays on literature, philosophy and social issues, two plays, four books of travelogues and a memoir in Malayalam, besides four books on comparative Indian literature in English. He has won 51 awards including the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award and National Sahitya Akademi Award, Knighthood by the Govt of Italy, Dante Medal by Dante Institute, Ravenna, International Poetry for Peace Award by the government of UAE, and Indo-Polish Friendship Medal by the Govt of Poland. If asked to describe Saadat Hasan Manto in one word, this reviewer would unhesitatingly call him an enigma. Strange as it may seem, Manto, arguably the greatest short story writer in Urdu, failed in Urdu in his high school exams. What is no less surprising is that, incurable alcoholic that he was — he asked for whiskey while being driven in an ambulance to the hospital on his fatal journey and was obliged by his family members — he always wrote ‘786’, the numerical symbol of Bismillah ir Rahman nir Raheem, at the top of his writings, be they for broadcasting, publishing or films.

If asked to describe Saadat Hasan Manto in one word, this reviewer would unhesitatingly call him an enigma. Strange as it may seem, Manto, arguably the greatest short story writer in Urdu, failed in Urdu in his high school exams. What is no less surprising is that, incurable alcoholic that he was — he asked for whiskey while being driven in an ambulance to the hospital on his fatal journey and was obliged by his family members — he always wrote ‘786’, the numerical symbol of Bismillah ir Rahman nir Raheem, at the top of his writings, be they for broadcasting, publishing or films. The biggest tragedy in Manto’s life is recalled by his friend Krishan Chander, another well-known fiction writer. It was the death of his eldest child, a year and a half old son. Writes Chander: “The armour of cynicism that he had built up all around himself was smashed to smithereens.” According to Manto’s eldest daughter Nighat, the loss affected her father so much that he was transformed from a social drinker to an irreversible alcoholic.

The biggest tragedy in Manto’s life is recalled by his friend Krishan Chander, another well-known fiction writer. It was the death of his eldest child, a year and a half old son. Writes Chander: “The armour of cynicism that he had built up all around himself was smashed to smithereens.” According to Manto’s eldest daughter Nighat, the loss affected her father so much that he was transformed from a social drinker to an irreversible alcoholic.