Indian language translations to look out for in 2021

The year 2020 was consumed wrestling with a predicament of unimaginable proportions. However, things were not so bleak for translated works in Indian literature. Last year was especially pivotal in driving home the perseverance of translations.

Transcending the challenges posed by the worldwide pandemic, translations shone in their roles of bridging cultures and amplifying under-represented voices in Indian-language literature. Masterpieces like Pandey Kapil’s Bhojpuri novel Phoolsunghi and pioneering Gujarati writer Dhumketu’s short story collection Ratno Dholi were made available to the English-speaking world for the very first time. They also served as a reminder that our journey through the nuanced and variegated depth of our literary roots is ever-continuous. It will keep leading us to chart new territories every year.

With that in mind, we have compiled a list of the upcoming translations from across Indian languages, which are currently gearing up for their much-anticipated release. Diverse and thought-provoking, add these riches of Indian language literature to your reading list for 2021:

HINDI

A Silent Place

by Vinod Kumar Shukla

Translated by Satti Khanna

Originally published in Hindi as Ek Chuppi Jagah, Vinod Kumar Shukla’s evocative novel tells the story of a grief-stricken forest that has been stunned into silence. It then follows the adventurous journey of a group of children as they devise schemes to restore the song of birds and murmurs of human voices into the forest. Translated as A Silent Place by Satti Khanna, the book also explores a profound human philosophy through the children who endeavoured to help the forest overcome its muteness.

Fifty-five Pillars, Red Walls

Fifty-five Pillars, Red Walls

by Usha Priyamvada

Translated by Daisy Rockwell

An iconic work of modern Hindi fiction, Usha Priyamvada’s Pachpan Khambe Laal Deewarein is hailed for its unflinching and deeply sensitive exploration of the emotional life of a single woman in Delhi in the 1960s. One of Priyamvada’s best-known works, we are eagerly waiting for one of our very first translations in collaboration with Speaking Tiger.

I Haven’t Seen Mandu

by Swadesh Deepak

Translated by Jerry Pinto

Recovering from a long spell of recurring bipolar psychosis, the celebrated Hindi writer Swadesh Deepak finished the manuscript of his memoir, Maine Mandu Nahin Dekha. Indian literature—in Hindi or any other language—has never produced anything as harrowing, yet strangely hypnotic as this. It remains one of the most revealing and powerful first-person accounts of mental illness and we are eagerly looking forward to Jerry Pinto’s translation to make it accessible to English readers.

Fragments of Happiness

by Shrilal Shukla

Translated by Niyati Bafna

In Shrilal Shukla’s Fragments of Happiness, an ordinary businessman from Delhi, Durgadas is apprehended for murder. Translated from Hindi by Niyati Bafna, the novel explores the psychological aftermath of the event by delving into the tumult of ordinary people coming to terms with their desires and helplessness.

MARATHI

Battlefield

by Vishram Bedekar

Translated by Jerry Pinto

A tragic love story between Herta, a Jew escaping Hitler’s Germany, and Chakradhar Vidhwans, a Marathi man returning from England to India, the novel was originally published as Ranaangan in 1939. Translated by Jerry Pinto, this novel is a rousing investigation of nationality against the backdrop of World War II. We are looking to read this fresh translation, sometime this year.

TAMIL

Generations

by Neela Padmanabhan

Translated by Kaa. Naa. Subramanium

Set in the 1940s around a community of Tamil speakers who live on the borders of modern Kerala, the novel offers a sensitively drawn profile of the passing of a traditional way of life into modernity and the nostalgia that comes with change. The book is expected to release this June, by Niyogi Books.

The Collected Stories of Imayam

Translated by Padma Narayanan

Imayam is one of the foremost and bestselling Dalit writers in Tamil, closely associated with the Dravidian movement and its politics. Speaking Tiger brings together his selected short stories in English for the very first time in this collection. We are eagerly looking forward to this one.

ASSAMESE

Five Novellas about Women

by Indira Goswami

Translated by Dibyajyoti Sarma

From the pioneer of feminist Assamese literature, here’s a cross-sectional portrayal of her lesser-known writings with a special focus on women. The lives of the rural poor, the situation of widows, the plight of the urban underclass and various social constraints under which people are forced to live, are depicted in these impactful narratives. The book is slated to release this July, by Niyogi Books.

Incidentally, we have learnt of a collection called Tales from Assam by Ranjita Biswas, that is on the cards later this year, by Rupa Publications.

MALAYALAM

The Book of Passing Shadows

by C.V. Balakrishnan

Translated by T. M. Yesudasan

Set in a Malabar village of Christian settlers, C.V. Balakrishnan’s The Book of Passing Shadows resonates with the pathos of the human spirit caught in the travails of earthly life. Translated by T.M.Yesudasan, the novel has remained popular with readers since the Malayalam original Aayusinte Pusthakam was first published in 1984.

Theeyoor Chronicles

by N. Prabhakaran

Translated by Jayasree Kalathil

Theeyoor Chronicles by N. Prabhakaran follows the trail of a journalist who visits Theeyoor or ‘the land of fire’ to investigate uncanny happenings. Interspersed with history, myths, nature, political events, and everyday concerns of ordinary people—this novel is widely regarded as a masterpiece of contemporary Malayalam literature. We can’t wait for its release.

Lesbian Cow and Other Stories

by Indu Menon

The most outspoken contemporary feminist writer from Kerala, many consider Indu Menon a successor to Kamala Das, having inherited the same progressive outlook. In Lesbian Cow and Other Stories, she uses raw images, bolder language and empathetically records the lives of marginalised sections of society.

Collection of Stories

by Shihabudheen Poythumkadavu

Translated by J Devika

On the collection, translator J Devika says that ‘Shihabudheen’s stories are sometimes realistic, sometimes terrifyingly not…you can sense in his writing the deep anxieties of the Muslim male and all kinds of inversions…and crossings between the human and non-human universes.’ We wonder what this abstract collection would read like.

KANNADA

This Life at Play: A Memoir

by Girish Karnad

Translated by Srinath Perur and Girish Karnad

First published in Kannada in 2011—and being made available to English readers for the very first time—This Life at Play provides an unforgettable glimpse into the life of a towering figure on India’s cultural scene—actor, film director, writer, and playwright—Girish Karnad.

GUJARATI

Krishnayan

by Kaajal Oza Vaidya

Kishnayan is indisputably Gujarati literature’s biggest bestseller, having sold over 200,000 copies and gone into 28 editions. This tender, lyrical novel starts when Krishna is injured by Jara’s arrow, and gives us glimpses into Krishna’s last moments on Earth. The most important women in his life—Radha, Rukmini, Satyabhama and Draupadi—appear before him. The novel is stitched together with what they meant to Krishna.

SPECIAL MENTION

Voices from the Lost Horizon: Stories and Songs of the Great Andamanese

by Anvita Abbi

Voices from the Lost Horizon is the first-ever compilation of folk tales and songs, rendered to Prof. Abbi and her team, by the Great Andamanese people in local settings. It comes with audio and video recordings of the stories and songs to retain the originality of the oral narratives.

BENGALI

Kaste

by Anita Agnihotri

Translated by Arunava Sinha

Through the lives of farmers, migrant labourers and activists in Marathwada and western Maharashtra, Anita Agnihotri’s Kaste illuminates a series of intersecting and overlapping crises: female foeticide, sexual assault, caste violence, feudal labour relations, farmers’ suicides and climate change in all its manifestations. Translated as The Sickle by Arunava Sinha, this gripping fictional narrative tells the darkest truths about contemporary India. It is set to release this March, by Juggernaut Books.

Ether Army

by Sirsho Bandopadhyay

Translated by Arunava Sinha

This powerful novel narrates the true story of a handful of broadcasters in the port city of Chittagong in East Pakistan, who joined the Liberation war with the only weapon they had: a radio transmitter. We are hoping Westland Books releases it on the eve of the 50th anniversary of the Bangladesh Liberation War.

Mahanadi: A Novel about a River

by Anita Agnihotri

Translated by Nivedita Sen

Woven around the mighty river Mahanadi that originates in Chattisgarh, Anita Agnihotri’s novel documents the life and struggles of people through the confluence of myths, legends and archaeological anecdotes. First published in Bengali (2015), this translation by Nivedita Sen is expected to be released in May through Niyogi Books.

Amrita Kumbher Sandhane

by Samaresh Basu

Written by the Sahitya Akademi-winning Bengali author Samaresh Basu, Amrita Kumbher Sandhane is narrated through the gaze of the protagonist, who has come to the Kumbh Mela—one of the largest Indian religious fairs —not out of any religious sentiment, but merely to see and understand people.

Chandal Jibon Trilogy — Part 2

by Manoranjan Byapari

Translated by V. Ramaswamy

While The Runaway Boy was released late last year, it introduced us to Jibon, who arrives at a refugee camp in West Bengal with his Dalit parents and later runs away to Calcutta to earn his living, we are anxiously awaiting Part 2 of the trilogy.

Chhera Chhera Jibon

by Manoranjan Byapari

Translated as A Tattered Life, Manoranjan Byapari’s most recent standalone novel is about a boy called Imon who goes to jail in his mother’s arms, and is let out in his early twenties long after his mother has passed.

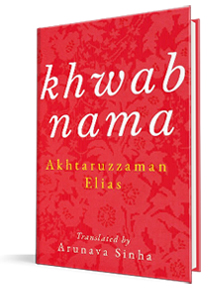

Khwabnama

by Akhtaruzzaman Elias

Translated by Arunava Sinha

Published in 1996, Khwabnama captured the variegated experiences of the people of Bengal (present-day Bangladesh) during the turbulent times of the 1947 partition. Best known as critically acclaimed author Akhtaruzzaman Elias’s magnum opus, the novel also delves into the socio-political realities of that period—the communal riot, the rebellion of the peasants against the landlords and the conflict between different ideologies, among others. The English translation by Arunava Sinha will be released in July by Penguin India.

“Where the mind is without fear

“Where the mind is without fear

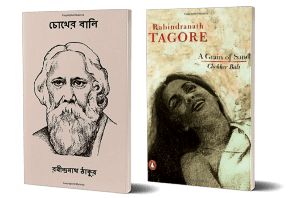

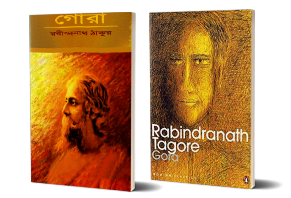

GORA (1909)

GORA (1909)

SHESHER KABITA (1929)

SHESHER KABITA (1929) We met in 1965, remember? In the MA English Literature class, taught by many luminaries, among whom the most brilliant were Nissim Ezekiel and Dr RB Patankar. You and Yasmeen Lukmani and I would traipse over to Dr Patankar’s room in the university building at Fort to hang around. That’s what it was. Hanging around, with cups of tea, and Dr Patankar sitting across the table, his fingertips together, and a characteristic half- smile lighting up his face. Often Dr MP Rege dropped in too, and our debates rose to some other level. How we argued. We were allowed to do that in those glorious days when ideas could be freely exchanged and challenged. You once said to me, “I wonder how you would look with your mouth shut.”

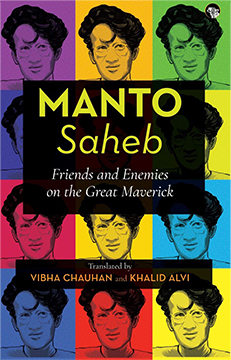

We met in 1965, remember? In the MA English Literature class, taught by many luminaries, among whom the most brilliant were Nissim Ezekiel and Dr RB Patankar. You and Yasmeen Lukmani and I would traipse over to Dr Patankar’s room in the university building at Fort to hang around. That’s what it was. Hanging around, with cups of tea, and Dr Patankar sitting across the table, his fingertips together, and a characteristic half- smile lighting up his face. Often Dr MP Rege dropped in too, and our debates rose to some other level. How we argued. We were allowed to do that in those glorious days when ideas could be freely exchanged and challenged. You once said to me, “I wonder how you would look with your mouth shut.” If asked to describe Saadat Hasan Manto in one word, this reviewer would unhesitatingly call him an enigma. Strange as it may seem, Manto, arguably the greatest short story writer in Urdu, failed in Urdu in his high school exams. What is no less surprising is that, incurable alcoholic that he was — he asked for whiskey while being driven in an ambulance to the hospital on his fatal journey and was obliged by his family members — he always wrote ‘786’, the numerical symbol of Bismillah ir Rahman nir Raheem, at the top of his writings, be they for broadcasting, publishing or films.

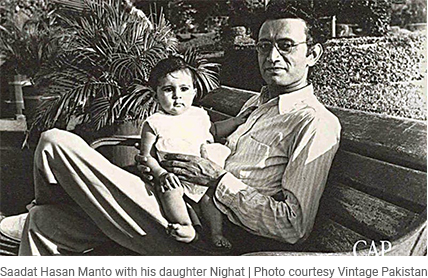

If asked to describe Saadat Hasan Manto in one word, this reviewer would unhesitatingly call him an enigma. Strange as it may seem, Manto, arguably the greatest short story writer in Urdu, failed in Urdu in his high school exams. What is no less surprising is that, incurable alcoholic that he was — he asked for whiskey while being driven in an ambulance to the hospital on his fatal journey and was obliged by his family members — he always wrote ‘786’, the numerical symbol of Bismillah ir Rahman nir Raheem, at the top of his writings, be they for broadcasting, publishing or films. The biggest tragedy in Manto’s life is recalled by his friend Krishan Chander, another well-known fiction writer. It was the death of his eldest child, a year and a half old son. Writes Chander: “The armour of cynicism that he had built up all around himself was smashed to smithereens.” According to Manto’s eldest daughter Nighat, the loss affected her father so much that he was transformed from a social drinker to an irreversible alcoholic.

The biggest tragedy in Manto’s life is recalled by his friend Krishan Chander, another well-known fiction writer. It was the death of his eldest child, a year and a half old son. Writes Chander: “The armour of cynicism that he had built up all around himself was smashed to smithereens.” According to Manto’s eldest daughter Nighat, the loss affected her father so much that he was transformed from a social drinker to an irreversible alcoholic.

Pather Panchali by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay

Pather Panchali by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay