May 21, 2019

Indian Novels Collective

BOOK EXCERPT

Seeing but not SEEN

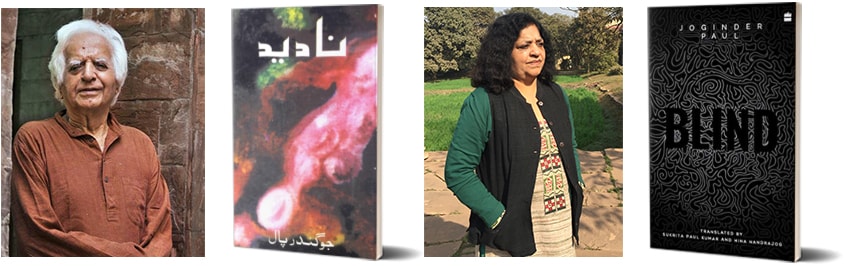

Known as one of the greatest storytellers of the Partition, Joginder Paul has been the recipient of important literary awards, such as the International Award for Urdu Writing from Qatar, SAARC Life Achievement Award, Iqbal Samman, Ghalib Award, Bahadur Shah Zafar Award and many others. His fiction has been translated into several languages. With his unique writing style and choice of themes, he is known as one of the most innovative writers in Urdu.

Joginder Paul migrated from Sialkot (now in Pakistan) to Ambala (India) in 1947, at the time of Partition, after which he married and left for Kenya where he lived for nearly 15 years. The experience of being a refugee and that of ‘exile’ reflected in a lot of his short and long fiction writings. He was familiar with multiple languages, with Punjabi as his mother tongue and school education in Urdu. Post this he pursued a Masters degree in English and taught literature until he retired as the principal of a college in Aurangabad. Joginder Paul chose to write in Urdu, with a conviction that Urdu is ‘not a language but a culture’.

Grounded in human suffering and exposed to continental fiction, he found his own distinctive style of writing. While Joginder Paul’s first collection of short stories, Dharti ka Kaal, carried stories of Africa, the subsequent collections of his short stories project a deep concern for social issues, poverty and hunger, mostly in the Indian context. His novel Khwabro has been widely discussed as a poignant Partition novel with a television film made on it. The four volumes of flash fiction by him established him as a pioneer in the oeuvre. Each of his stories came to him with its own specific language and style, shape and size, as dictated by its own experience and content. Joginder Paul added new dimensions to Urdu fiction, both in content as well as form.

It was the lasting experience of visiting a blind home in Kenya which several decades later compelled him to write his novel Nadeed, translated to English, as Blind by his daughter Sukrita Paul Kumar and co-translated by Hina Nandrajog. The English translation works towards maintaining the metaphorical significance of the word ‘Blind’ and the inter-relation of the allegorical and physical blindness in the narrative projected in Nadeed. Sukrita Paul Kumar and Hina Nandrajog, attempt to transpose the metaphysical dimensions of blindness, present in Joginder Paul’s work.

Here is an excerpt from the translation:

Sharfu

Each of us has his own way of seeing. Who can tell how the other sees? As for me, I see the whole world within myself – lofty mountain peaks that pierce my insides, wide rivers in whose eddies I sometimes get trapped; dashing against the rocks, I smash into pieces, but my banks gather all the pieces from the flowing waters, put them together and carry me to a safe and secluded maidan.

Within me lies the world-of-worlds. Many places in this world have been torn and worn by cruel seasons, but somehow I manage to patiently build kutcha-pukka bridges so that no part of me remains isolated. I arrive wherever I wish to reach the very moment the thought of getting there comes to me. I live in every speck and atom of this universe of mine.

No, I am not making any claim to godhood! The truth is that I was born blind and I lie inside myself quietly. Quietly? No, that’s a lie! And … and it is also a lie that all of my fragments lie scattered. The truth is that all my bridges are broken. I comfort myself in vain. In fact, blind as I am, I’m unable to reach anywhere; even if I have to reach my mouth from my ears, I fall with a thud on the way.

The mention of mouth, ears and all reminds me of a curious incident that took place a few days ago.

The three of us from our Home for the Blind were sitting together after lunch when Bhola said, Yaaro, life stinks but if we spend it together it won’t be so bad.

Bhola always comes out with meaningful observations, so both of us listen to him very attentively.

The distance from inside to outside stretches across in an awfully tangled length, yaaro! I keep falling on my face even if I have to travel from my head to my belly.

Yes, Bhola, precisely! This is the problem when it is one’s fate to fill the belly with just thoughts. And then with a full belly, who can remember the way back to the head?

Shall I ask you something, Bhola? Why return to the head anyway? As for me, once my stomach is full I lie crouched in the middle with my legs under my belly.

That’s it, Bhola. A full belly makes one feel one is on a swing.

But for how long does a full belly remain full, yaaro?

When the belly gets empty, the swing snaps, the bones crack, and the person feels them stabbing his feet.

Yes, we should get back to the head as soon as the belly is full. sss

But that is the dilemma! Once the belly is full, one can’t figure out the way back home.

Right, Bhola! A man’s head is his home … but how to fill our bellies if we don’t step out of the house?

And how to go back when the belly is full?

Excerpt published with the permission of Sukrita Paul Kumar. The book is available in paperback and e-book format and is published by Harper Perennial.

For reading the original in Urdu, please visit http://bit.ly/2WMAznS

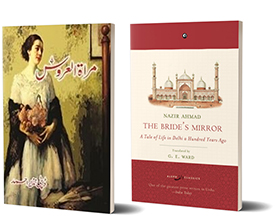

Mirat-al-Urus by Nazir Ahmad

Mirat-al-Urus by Nazir Ahmad

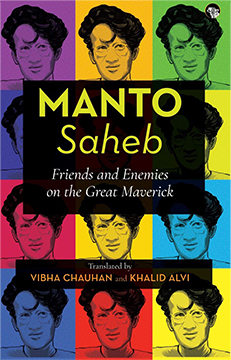

If asked to describe Saadat Hasan Manto in one word, this reviewer would unhesitatingly call him an enigma. Strange as it may seem, Manto, arguably the greatest short story writer in Urdu, failed in Urdu in his high school exams. What is no less surprising is that, incurable alcoholic that he was — he asked for whiskey while being driven in an ambulance to the hospital on his fatal journey and was obliged by his family members — he always wrote ‘786’, the numerical symbol of Bismillah ir Rahman nir Raheem, at the top of his writings, be they for broadcasting, publishing or films.

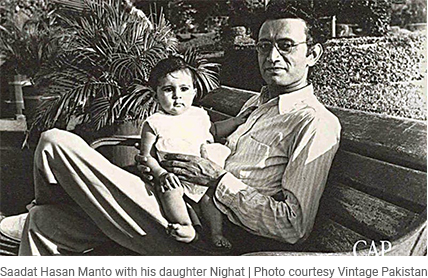

If asked to describe Saadat Hasan Manto in one word, this reviewer would unhesitatingly call him an enigma. Strange as it may seem, Manto, arguably the greatest short story writer in Urdu, failed in Urdu in his high school exams. What is no less surprising is that, incurable alcoholic that he was — he asked for whiskey while being driven in an ambulance to the hospital on his fatal journey and was obliged by his family members — he always wrote ‘786’, the numerical symbol of Bismillah ir Rahman nir Raheem, at the top of his writings, be they for broadcasting, publishing or films. The biggest tragedy in Manto’s life is recalled by his friend Krishan Chander, another well-known fiction writer. It was the death of his eldest child, a year and a half old son. Writes Chander: “The armour of cynicism that he had built up all around himself was smashed to smithereens.” According to Manto’s eldest daughter Nighat, the loss affected her father so much that he was transformed from a social drinker to an irreversible alcoholic.

The biggest tragedy in Manto’s life is recalled by his friend Krishan Chander, another well-known fiction writer. It was the death of his eldest child, a year and a half old son. Writes Chander: “The armour of cynicism that he had built up all around himself was smashed to smithereens.” According to Manto’s eldest daughter Nighat, the loss affected her father so much that he was transformed from a social drinker to an irreversible alcoholic.