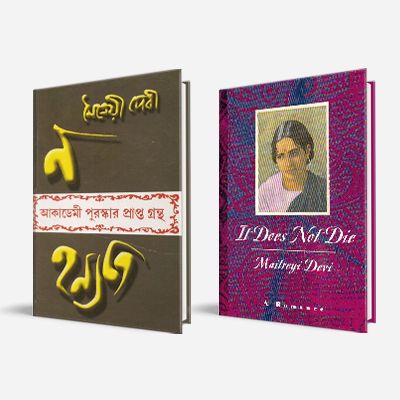

Na Hanyate

By Maitreyi Devi

Translated into English as It does not die by University of Chicago Press (1995)

Originally published in 1974, Maitreyi Devi’s Sahitya Akademi-winning novel Na Hanyate was translated into English as It Does Not Die. The autobiographical novel was written in response to Romanian philosopher Mircea Eliade’s book La Nuit Bengali (titled Bengal Nights in English), which related a fictionalized account of their romance during Eliade’s visit to India. Against a rich backdrop of life in an elite, upper-caste Hindu household, Devi powerfully recreates the confusion of a precocious girl child and depicts a moving account of a thwarted first love fraught with cultural tensions, of false starts and enduring regrets with a contemplative depth. Today, both those novels, written forty years apart, are often read together as reflecting the emotional aftermath of their doomed romance from two ends of the spectrum. Devi’s novel consolidates its profound position as a powerful analysis of what happens when the collisions between innocence and experience, enchantment and disillusion, and cultural difference and colonial arrogance collide. Thus, despite nominally relating the same events, they present themselves differently in their viewpoints and storylines. What startled the readers and justifiably took the literary world by storm was Devi’s bold, unabashed portrayal of her love in a lucid and disarmingly impassioned manner which catapulted her to great fame and established her as a litterateur to be reckoned with. According to the author and academic Ginu Kamani, “I was riveted by the boundary-less form of her narrative, dipping in and out of poetic prose and historical reminiscence… I have never read such a book written by an Indian woman from India, and especially by one of her generation.” The book received the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1976.

About the Author

Maitreyi Devi (1914–1990) was a Bengali-born Indian poet and novelist. She was the daughter of philosopher Surendranath Dasgupta and protegée of poet Rabindranath Tagore. Her first book of verse Udarata appeared when she was sixteen, with a preface by Rabindranath Tagore. She had written prolifically on Rabindranath and her works include Mungpute Rabindranath (Tagore in Mungpu) which she had herself translated into English as Tagore by Fireside, Grihe o Vishwe (Tagore at Home & the World), Rabindranath—the man behind his poetry and Swarger Kachakachi (Close to Paradise). The last is an anthology of letters exchanged between Tagore, her father and herself. Apart from being a writer, she also set up an orphanage for needy children later in her life.

Hajar Churashir Ma

By Mahashweta Devi

Originally published in 1974, Mahasweta Devi’s best-known novel Hajar Churashir Ma was translated into English as Mother of 1084 by Samik Bandyopadhyay (2010). It is a heart-breaking and yet coldly analytical story of a loving mother who is suddenly informed of her grown-up son’s death. Identified only as No. 1084 by the morgue authorities, the young man was killed in one of the many false encounters that the police used in the 1970s in Bengal to eliminate revolutionary Naxals.

A year after his death, she begins to piece together the story of his involvement with the Naxal movement, getting in touch with his former comrades and learning the details. The novel offers a unique perspective on the armed political movement that shook Bengal in the 1970s, claiming victims among both the urban youth and the rural peasantry, leaving its impact not just on the political and administrative landscape, but also on the families of those who died. It won the Jnanpith Award in 1996.

Crisp and incisive in capturing the thought processes of a generation and the turmoil in the cosy construct of the middle-class family, Mother of 1084 is still a truly moving human document. In an interview, Devi said that she wrote it in four days flat, almost as a command performance in response to the requests of urban Naxalites who said she only wrote about the tribal community but never about them.

About the Author

Mahasweta Devi (1926-2016) was one of the foremost writers in Bengali.

She is not only known for her political writing style but her immense contribution towards communities of landless labourers of eastern India where she worked for decades. Her intimate connection with these communities allowed her to understand and begin documenting grassroots-level issues, giving her stories a distinct socio-political authenticity and empathy. Her impressive body of work includes novels, short stories, children’s stories, plays and activist literature. She received the Padma Shri (1986) and Padma Vibhushan (2006), the Ramon Magsaysay Award (1997) and was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2012, and remains one of the most studied and translated Bengali authors today.

Also read

Aranayer Adhikar

Mahasweta Devi had woven a historical fiction around the legend of Birsa Munda in her 1977 novel Aranyer Adhikar (Rights of the Forest). Using her research about his life, as well as her experience working as an activist in tribal areas, she traces the life of this tribal leader, folk hero, and freedom fighter through his trials and tribulations in the late 19th century, particularly the tribal uprising he led against the British. While the story sticks largely to its historical authenticity, it is in the dramatization and contextualisation of the events that the novel shines. It received the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1979.

Jhansir Rani

Mahasweta Devi’s prolific writing career was launched with the publication of her first book Jhansir Rani (1956) which has been translated into English as The Queen of Jhansi (Seagull Books, 2010). Mahasweta Devi undertook extensive research that encompassed family reminiscence, oral literature, local histories, and more traditional sources. From these she wove a very personal history of a legendary Indian heroine—building a detailed picture of Lakshmibai, the Queen of Jhansi, as a complex, spirited, full-blooded woman who grew from a free-spirited child into an independent young leader and led her troops against the British in the uprising of 1857, which is now widely described as the first Indian War of Independence. Simultaneously a history, a biography, and an imaginative work of fiction, this book is a valuable contribution to the reclamation of history by feminist writers.

Shamba

By Samaresh Basu 'Kalkut'

Shamba (1978) is an interesting modern interpretation of the Puranic tales. In fact, it was unique in its time for not being a purely socially realist work, but instead a transformation of an ancient legend to modernity. Written under his nom de plume ‘Kalkut’ (Deadly Poison), under which Basu published travelogues, this eponymous novel is less travel across land and more travel across time which takes the author right ‘from the bank of the Caspian to Kuru Panchala’ ending at Dvaravati, the home of the Yadavas. Guided by Suta, the official Puranic narrator, the author finds himself traversing the ‘true’ history of Aryan expansion where all characters from Indra to Krishna are ‘real’. The story depicts the life of Shamba, the most beautiful prince among the Yadavas, who is cursed with leprosy by his father, in a fit of acute sexual jealousy, roused by the popularity and attraction of Shamba with Krishna’s sixteen thousand women. Shamba searches for a cure helplessly, aided by a leper Neelakshi, and is finally healed by the followers of the Sun-god, to whom he dedicates his life and wealth. Thus, the book deals with themes of forgiveness, disability, egalitarianism, all through a meld of Buddhism, Hinduism, and modern Marxism, egalitarianism and feminism. In the words of critic Esha Dey, this makes the novel “existential history par excellence… [which] renders all encounters with reality a see-saw process of experience and analysis”. It received the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1980.

About the Author

A prolific writer with more than 200 short stories and 100 novels, including those written under the aliases ‘Kalkut’ and ‘Bhramar’, Samaresh Basu is a major figure in Bengali fiction. His life experiences influenced his writings and his gritty fiction featured workers, revolutionaries, and radicals who fought society and their own demons and disenchantment. Two of his novels were briefly banned on charges of obscenity. He was an active member of the trade union and the Communist party for a period, and was jailed during 1949–50 when the party was declared illegal. While in jail, he wrote his first novel, Uttaranga, which was published in book form. He often wrote under the pen name ‘Kalkut’ or ‘Bhramar’.

Also read

Mahakaler Rather Ghoda (1977)

Originally published in 1977, Mahakaler Rather Ghoda (Horse to the Chariot of Time) has also been translated into English as Fever by Arunava Sinha (2016). Dark, powerful and full of ambiguities, the classic Mahakaler Rather Ghoda questions the human cost of revolution and its inevitable transience. A sensation in its time, it remains one of the greatest novels about the Naxalite movement which introduces the readers to Ruhiton Kurmi who has been in jail for seven years. Once a notorious Naxalite, he is now a withered shell; a man broken by torture, racked with fevers and sores. The fever which haunts Ruhiton emotionally and physically till the end becomes the symbol of decay, doubt and despair that encapsulates different kinds of sicknesses—in the socio-political power structure that Ruhiton and his comrades revolted against; in the gradual degeneration of the revolutionary movement; and in the betrayal of the toiling classes by the leaders of the revolution. This fever, which is the leitmotif of this novel, also becomes the title of the English translation.

Khandita (Dissevered)

Published seventy years after independence in 1985, Khandita (translated into English as Dissevered) raises the dominant questions of nationalism, identity crises, communal disharmony, and citizenship through a language of the gutters that ironically mimics the mores of civic society and asserts itself as the representative of the culture of the ‘urban popular’. The desire for unity of the nation felt by the three disoriented young protagonists, Gora, Bias, and Sati, is positioned against the territorial amputation born out of the Partition and the birth of a new nation (Bangladesh). This novella perhaps best illustrates Samaresh Bose’s genius as a writer who could vividly translate his experience of a crucial historical time in all its multiple complexities by weaving documentary reports into fiction and consummately depict the conflicting emotions experienced by ordinary folks on the eve of India’s independence as the narrative traverses the numerous facets of contemporary Bengali society.