15 Indian language women writers who should feature on your reading list

Updated on 8 March 2021

Often, the inspiration for a significant change is born from the most mundane of battles. Here are fifteen women from across Indian languages who gave us a glimpse of the inner workings of society from behind the four walls. Yet, their writing has radically questioned the patriarchy and societal inequality, and created an inclusive, thought-provoking representation of women in Indian literature.

On the occasion of International Women’s Day, let us celebrate them by celebrating their written word.

Qurratulain Hyder

Qurratulain Hyder

Urdu

One of the most outstanding literary names in Urdu literature, she is best known for her magnum opus, Aag Ka Darya. It tells a story that moves from fourth century BC to the post-Independence period in India and Pakistan. The female characters in most of her works are portrayed as independent individuals rather than being known through the male lens.

Further reading:

Safina-e-Gham-e-Dil (1952)

Translated into English as Ship of Sorrows by Saleem Kidwai (2019)

Spanning roughly three decades (1920s to 1950s), Safina-e-Gham-e-Dil is Qurratulain Hyder’s second work and derives its title from a poem by Faiz Ahmed Faiz. This novel is the coming-of-age story of a privileged set of six friends from Awadh that combines autobiography, fiction, and the documentation of time and place. The author debuts in this story as Anne Hyder and fictionalises her experience during the communal riots in Dehradun.

Aakhir-e-Shab ke Hamsafar (1979)

Translated into English as Fireflies in the Mist by the author

Set against the four decades of East Bengal’s history—from the dawn of nationalism in the 1930s to the restless aftermath of the bloody struggle for an independent Bangladesh—Aakhir-e-Shab ke Hamsafar is told through the impassioned voice of Deepali Sarkar. Hyder perceptively follows the trajectory of Sarkar’s life—from her secluded upbringing in Dhaka to becoming a socialist rebel, from her doomed love affair with Rehan Ahmed, a Muslim radical with Marxist inclinations, to her ultimate transformation as a diasporic Bengali cosmopolitan. The novel also explores the growth of tension between Bengal’s Hindus and Muslims who had once shared a culture and a history. Hyder received the Jnanpith Award in 1989 for this book.

Kamala Das

Kamala Das

Malayalam

Kamala Das is best known for her fearless and unapologetic treatment of female sexuality and questioning patriarchal norms. In her autobiographical novel, My Story originally published in Malayalam, titled Ente Katha, Das recounts the trials of her marriage and her painful self-awakening as a woman and writer.

Further reading:

Ente Katha (1973)

Translated into English as My Story (1988)

Originally published in Malayalam, this autobiographical novel provided a lens into the personal and professional experiences of Kamala Das, as an independent-minded woman navigating a patriarchal society. She introduced her readers to the concept of female sexuality, a notion that was non-existent in the conservative society of Kerala, until then. The book managed to evoke such a widespread reaction that it went on to become a cult classic and has stood the test of time, as one of the most enduring accounts of the life of a woman writer in India.

The Sandal Trees and Other Stories by Kamala Das

Translated into English by by V C Harris and C K Mohamed

Originally written in Malayalam by Kamala Das under the pen name Madhavikutty, the stories in this anthology (1995) deal with the nuances of human relationships and intrigues of love, life and death. The title story ‘The Sandal Trees’ is the English translation of ‘Chandanamarangal’ (1988) which charts a four-decade-long sexual and emotional relationship between two women that echoes the relationship between Kamala and the college girlfriend in My Story.

Mahasweta Devi

Mahasweta Devi

Bangla

Mahasweta Devi has been known as one of the boldest female writers in India. Her Bengali novel, Hazaar Chaurasi Ki Maa delved into the life of an ordinary Indian mother fighting against all odds to retain the memory of her dead son. Rudali, based on the life of Sanichari, a poor low-caste village woman and a professional mourner, is an ironic tale of exploitation and struggle and above all survival. A powerful text, Rudali is considered an important feminist text for contemporary India.

Further reading:

Jhansir Rani (1956)

Translated into English as The Queen of Jhansi by Sagaree and Mandira Sengupta (2010)

Mahasweta Devi’s prolific writing career was launched with the publication of Jhansir Rani (1956). Drawing from historical documents, folk tales, poetry and oral tradition—the novel constructs a detailed picture of the legendary Indian heroine, Lakshmibai, the Queen of Jhansi, who led her troops against the British in the uprising of 1857, now widely described as the first Indian War of Independence. Simultaneously a history, a biography, and an imaginative work of fiction, this book is an invaluable contribution to the reclamation of history by feminist writers.

Chotti Munda Ebong Tar Tir (1980)

Translated into English as Chotti Munda and His Arrow by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (2002)

The wide sweep of this novel ranges over decades in the life of Chotti, the hero of this epic tale, in which India moves from colonial rule to independence and then to the unrest of the 1970s. Written in 1980, it raises questions about the place of indigenous peoples on the map of India’s national identity, land rights and human rights, and the justification of violent resistance as the last resort of a desperate people.

Indira Goswami

Indira Goswami

Assamese

Indira Goswami continually addressed social injustices in her work. Her writing was spurred on by widowhood and social injustice. From her first novel, Neel Kanthi Braja (Shadow of Dark God, 1986), she examined the social and psychological deprivations of widowhood to Tej Aru Dhulire Dhushorito Prishtha (Pages Stained With Blood, 2001), where she writes about a young female teacher in the neighbourhoods of Delhi that have been affected by anti-Sikh riots in the wake of the assassination of Indira Gandhi by two of her Sikh bodyguards, her characters stand out and are imprinted in your mind forever.

Further reading:

Tej Aru Dhulire Dhushorito Prishtha (1986)

Translated into English as Pages Stained With Blood (2002) by Pradip Acharya

Considered a classic of modern Assamese literature, Tej Aru Dhulire Dhushorito Prishtha is, perhaps Goswami’s most famous work which first appeared in a serialised form in the monthly magazine Goriyoshi. Depicting the carnage of the 1984 anti-Sikh pogrom in Delhi after Indira Gandhi’s assassination through a semi-autobiographical lens, the novel is a first person account of a young woman who teaches at Delhi University.

Dontal Hatir Une Khowa Howdah (1986)

Translated as The Moth-Eaten Howdah of the Tusker by the author (2004)

Dontal Hatir Une Khowa Howdah revolves around the lives of Brahmin widows in a Vaishnavite satra of southern Kamrup in Assam, while also drawing upon the author’s own experiences of childhood and adolescence. Written in the dialect of the region, just after the Second World War, the novel holds up a powerful picture of transition that unsettles an apparently ‘timeless’ agrarian culture and the unchanging rhythms of orthodox religion within a layered, intricate social canvas. It was made into an award-winning film Adahya, by Santwana Bordoloi.

M K Indira

M K Indira

Kannada

Malooru Krishnarao Indira is a well-known Kannada novelist. Her most popular novel, Phaniyamma is based on the life of a child widow. It is a real-life story of a widow whom Indira knew during her childhood. While Gejje Pooje revolves around the life of prostitutes and the social stigma associated with it. Indira’s works have been a strong critique of various unjust practices related to women in the society.

Further reading:

Phaniyamma (1976)

Translated into English by Tejaswini Niranjana (1989)

Phaniyamma leads the austere life of a widow and never complains or rebels, but she does counter when inhumanity is sanctioned in the name of traditions. The novel works as a critique of the inherent social hypocrisy and demonstrates how Phaniyamma emerges as a powerful figure despite the atrocities posed by widowhood. The novel won the Karnataka State Sahitya Akademi Award and the English translation by Tejaswini Niranjana won the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1993. It was also adapted into a film that won several national and international awards.

Tungabhadra by M. K. Indira (1963)

M.K. Indira’s first novel Tungabhadra (1963) was a pioneering work. It portrayed the struggles and aspirations of rural women, and was able—through its use of evocative detail and regional dialect—to create a rural world with unprecedented realism. It also received the Karnataka State Sahitya Akademi Award.

Lalithambika Antharjanam

Lalithambika Antharjanam

Malayalam

Lalitambika Antharjanam, is popularly known for her short stories and powerful woman narratives in Malayalam literature. Her novel, Agnisakshi tells the story of a Nambudiri woman, struggling for social and political emancipation. The novelist highlights the women’s role in society and critiques the social institutions that limit women and curtail their freedom.

Further reading:

Agnisakshi (1976)

Translated into English as Agnisakshi: Fire, My Witness by Vasanthi Sankaranarayanan (2015)

Set against the history of Kerala, and the life, customs, habits and culture of the Namboodiri community alongside the Indian National Freedom struggle, it also highlights a woman’s struggle for social and political emancipation. The narrative follows three strong-willed female characters – Unni, Thankam and Tethi, as they struggle to search for their own freedom from the rigid and oppressive structures of Brahmanical patriarchy. The novel received the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1977.

Cast Me Out if You Will: Stories and Memoir (1998)

Translated into English by Gita Krishnankutty

Offering a chilling testimony to the brutal oppression suffered by women at all levels of Indian society, Cast Me Out if You Will (1998) is a unique collection of short stories and personal memoirs, which captures early moments in India’s nationalist and feminist movements. A compilation representing half a century of writing and activism— this is the ideal introduction to one of India’s best-loved and foremost feminist authors.

Bama

Bama

Tamil

Bama, the Tamil, Dalit, feminist novelist who rose to fame with her autobiographical novel Karukku, which chronicles the joys and sorrows experienced by Dalit Christian women in Tamil Nadu. They portray caste-discrimination practised in Christianity and Hinduism. Bama’s works are seen as embodying Dalit feminism and are famed for celebrating the inner strength of the subaltern woman.

Further reading:

Sangati (1994)

Translated into English as Sangati: Events by Lakshmi Holmström (2005)

Published in 1994, Sangati seeks to create a Dalit-feminist perspective and explores the impact of manifold social inequities, compounded by poverty suffered by Dalit women. Translated from Tamil by Lakshmi Holmström as Sangati: Events, it rejects all received notions of what a novel should be, delves deep into a community’s identity and underlines the fighting spirit of the Paraiya women against the double-edged oppression of caste and gender discrimination.

Kusumbukaran (1996)

Translated into English as The Ichi Tree Monkey: New and Selected Stories by N. Ravi Shanker (2021)

This collection features the Dalits of rural Tamil Nadu as the protagonists and celebrates the everyday acts of rebellion and fortitude. Translated from Tamil by N. Ravi Shanker, this recently released short-story collection bears testament to the raw energy and vitality one can always encounter in Bama’s widely acclaimed writing.

Kundanika Kapadia

Kundanika Kapadia

Gujarati

Kundanika Kapadia is a Gujarati novelist, story writer and essayist who won the Sahitya Akademi Award for Gujarati in 1985 for Sat Pagala Akashma – a revolutionary feminist work in Gujarati. The novel raises questions about the status of a married woman accorded to her by a male-dominated society and struggles to find an equal voice and liberty for women.

Krishna Sobti

Krishna Sobti

Hindi

Krishna Sobti is popularly known for her bold and daring characters in her novel. Her most acclaimed novel Mitro Marajani is about a young married woman’s exploration and assertion of her sexuality, which set the Hindi literary world aflame and is seen as a major feminist work.

Forthright as ever, Sobti said, “I don’t like being called a ‘woman writer’. I would rather be called a writer who is also a woman…”

Further reading:

Zindaginama (1979)

Translated into English as Zindaginama by Neer Kanwal Mani and Moyna Mazumdar

Set in the small village of Shahpur in undivided Punjab, Zindaginama is a magnificent portrait of India on the brink of its cataclysmic division. Detailing the intricately woven personal histories of a wide set of characters, Krishna Sobti’s magnum opus imbues each with a unique voice, enriching the text with their peculiar idiom. Described by Ashok Vajpeyi as an ‘abridged Mahabharata’, it received the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1980.

Gujrat Pakistan se Gujarat Hindustan (2016)

Translated into English as A Gujarat Here, A Gujarat There by Daisy Rockwell (2019)

Part novel, part memoir, part feminist anthem, A Gujarat Here, A Gujarat There is not only a powerful tale of Partition loss and dislocation, but also charts the odyssey of a spirited young woman determined to build a new identity for herself on her own terms.

Irawati Karve

Irawati Karve

Marathi

Though not a novelist, Irawati Karve’s refreshing approach to Mahabharata in her collection of essays, Yuganta: The End of an Epoch, has left a lasting mark in literature. Scientific in spirit, yet appreciative of the literary tradition of the Mahabharata, she challenges the familiar and formulates refreshingly new interpretations, all the while refusing to judge the characters harshly or venerate blindly. Yuganta received the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1968, making Karve the first female author from Maharashtra to receive it.

Amrita Pritam

Amrita Pritam

Punjabi

Leading poet, novelist and essayist, Amrita Pritam was the first Punjabi woman litterateur to be felicitated with both, the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1956 for her magnum opus Sunehade and the Jnanpith Award in 1982 for Kagaz te Canvas. A crusader for gender equality and a woman’s right to live, love and write sans constraint, the iconic writer paved the way for many young writers through her writing and life. Recipient of the Padma Shri and the Padma Vibhushan, Pritam authored 100 books in different genres—poetry, fiction, essays, biographies, memoirs—as well as a famous autobiography titled Raseedi Ticket (The Revenue Stamp, 1976).

Further reading:

Pinjar (1956)

Translated into English as Pinjar: The Skeleton and Other stories by Khushwant Singh (2005)

Pinjar relates the story of a Sikh girl who was abducted by a Muslim because of a land feud and she chooses to remain with him rather than be rehabilitated in India after Partition. Translated by Khushwant Singh, the novel is widely considered one of the outstanding works of Indian fiction which engaged with the Partition from a woman’s perspective.

Raseedi Ticket (1976)

Translated as The Revenue Stamp (2015)

Maintaining a non-linear, fractured rhythm, it includes recollections of her travels, the making of specific books, references to fellow-writers and snatches of conversations with loved ones, but the bulk of the text contains reflective lines and notes to herself that she has learnt from her life experiences, the most memorable and sustained being love.

Popati Hiranandani

Popati Hiranandani

Sindhi

A versatile Sindhi writer, a forthright feminist, and an outstanding social activist, Popati Hiranandani was a formidable presence in twentieth-century Sindhi literature. Recipient of several awards, including the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1982 for her autobiography, Hiranandani tried her hand at multiple genres: the novel, short fiction, poetry and biography, as well as literary criticism. Her works not only depicted the urban milieu of Sindhi culture, but also delved deep into the life of Sindhi middle-class and the plight of women in the social structure. Among the several works she published are poetry collections: Ruha sandi runch (1975), Man Sindhini (1988), short stories: Pukar (1953), Zindagi-a-ji-photri (1993), novel: Sailab zindagi-a-jo (1980), etc.

Further reading:

Munhinji-a Hayati-a Jaa Sona Ropa Varqa by Popati Hiranandini (1980)

Translated into English as The Pages of My Life: Autobiography and Selected Stories by Jyoti Panjwani (2010)

The award-winning autobiography poignantly captures the two vastly different worlds of pre- and post-Partition India through the author’s journey as a homeless, community-less, displaced woman. Translated as The Pages of My Life: Autobiography and Selected Stories, it also provides remarkable insights into the Sindhi society, and the social and political upheaval following the great tragedy overtaking the country.

Yaddanapudi Sulochana Rani

Yaddanapudi Sulochana Rani

Telugu

Considered among the top fiction writers of her time, novelist Yaddanapudi Sulochana Rani heralded a new era in Telugu fictional literature in the decades between the 70s and early 80s. She introduced pulp literature to a new generation and brought novels to the mainstream, in Telugu. Her prolific writings reflected contemporary trends, complexities of urban relationships and the working of a woman’s mind. Employing her signature nostalgic style, the immensely popular writer threw new light on romance and popularised reading among the middle-classes, especially women. Some of her best-known works, which used to be serialised in Telugu magazines, include Secretary, Jeevana Tarangalu, Kalala Kougili, etc. Many of her literary works have been adapted into films and TV serials.

Further reading:

Meena

The novel revolves around the eponymous character Meena, her silent rebellion against her mother, her escape from an unwanted wedding, her attempt to reunite feuding families, and how she succeeds in marrying the love of her life, against all odds.

Secretary

Narrating the romance between Jayanthi—who joins as a secretary in an elite ladies’ society ‘Vanitha Vihar’ and industrialist Rajasekharam—the novel Secretary created tropes of a wealthy, stylish landlord, and luxurious cars that captured the fantasies of many. Written 50 years ago, the universal appeal of this bestseller still continues to charm the readers. It remains relevant in its portrayal of social reality, celebration of self-made, modern women and their quest to break free from punitive norms. It was also adapted into a 1976 Telugu film and won Rani laurels across the commercial stream.

Ismat Chughtai

Ismat Chughtai

Urdu

Universally regarded as one of the four pillars of modern Urdu fiction, Ismat Chughtai has received many awards and accolades, including the Padma Shri, in 1976. Her formidable body of work, including short stories, screenplays, novels, novellas, sketches, plays, reportage and even radio plays, created revolutionary feminist politics and aesthetics in twentieth-century Urdu literature. Her style was bold, innovative, rebellious, and unabashedly realistic. Ismat analysed feminine sexuality, middle-class gentility, and other evolving conflicts in modern India.

Further Reading:

Tedhi Lakeer (1943)

Translated into English as The Crooked Line by Tahira Naqvi (2006)

Published in 1943, Tedhi Lakeer is centered on Shamman who grows from being a rebellious, independent-minded girl to a politically-conscious feminist activist involved in the Indian independence struggle. In this critically-acclaimed, semi-autobiographical novel, Ismat Chughtai exposes the intellectual and emotional conflicts against the backdrop of an enormous socio-political canvas.

Dil ki Duniya (1918)

Translated as A Chughtai Collection: with The Quilt and Other Stories & The Heart Breaks Free & The Wild One by Syeda Hameed and Tahira Naqvi (2003)

Narrated in the first person from a child’s point of view, the novella follows the lives of a varied group of women living in a conservative Muslim household in Uttar Pradesh. Dil Ki Duniya, much like Tedhi Lakeer, is autobiographical in nature as Chughtai draws on her childhood memories of life in Bahraich.

Basanta Kumari Patnaik

Basanta Kumari Patnaik

Odia

The first and only Odia woman writer to have received the Atibadi Jagannath Das award—the highest award of the Odisha Sahitya Akademi—Basanta Kumari Patnaik was an eminent novelist, short story writer, playwright, poet and essayist. Her notable short story collections include Sabhyatara Saja, Palata Dheu, Jibana Chinha. The three novels that established her reputation as a major writer of fiction are Amada Bata (translated as The Untrodden Path), Chorabali and Alibha Chita (translated as The Undying Flame). Considered one of the pioneers in Odia literature, Patnaik’s writings reflect a deep understanding of the domestic and social world of twentieth century Odisha.

Reading Recommendations:

Amada Bata

Translated into English as The Untrodden Path

Amada Bata became the first Odia novel to be successfully adapted into a memorable film and remains an iconic classic, both in Odia fiction and cinema. Set in a middle-class household, the novel’s protagonist Maya is a remarkably perceptive and resilient character, gifted with the ability to dissect the ‘veneer of civilization’ at large, through its practice of customs and rituals. Patnaik, in Amada Bata, compels readers to rethink the fundamental ethical assumptions associated with the duties and responsibilities of individual women.

Do you have a list of your own? Do share it with us in the comments below.

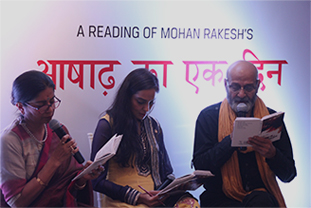

The Monsoon Reading of ‘Ashaad Ka Ek Din’ —the first modern Hindi play by Mohan Rakesh held at Jindal Mansion on Friday, July, 5, 2019 was attended by a motley group of theatre lovers and some renowned artistes. Sangita Jindal, Amrita Somaiya, Ashwani Kumar, Anuradha Parikh — the core group members of Indian Novels Collective, were all present to support and conduct the evening’s proceedings. Ashwani Kumar began the event by shedding light on the iconic play by Mohan Rakesh and introducing the performers for the evening with verses from Kalidas, celebrating clouds and rains in the city. He also thanked veteran actor, Saurabh Shukla and curator of Literature Live, Anil Dharkar for gracing the occasion. Mrs Sangita Jindal, chairperson of JSW foundation, extended a warm welcome and spoke passionately about JSW foundation’s association with Indian Novels Collective and the group’s translation project that aims to make Indian language classics accessible to English readers and popularise readings of classic Indian literature. She urged the audience to make the effort to broach Indian languages and keep the traditions and cultures flourishing, with adequate support.

The Monsoon Reading of ‘Ashaad Ka Ek Din’ —the first modern Hindi play by Mohan Rakesh held at Jindal Mansion on Friday, July, 5, 2019 was attended by a motley group of theatre lovers and some renowned artistes. Sangita Jindal, Amrita Somaiya, Ashwani Kumar, Anuradha Parikh — the core group members of Indian Novels Collective, were all present to support and conduct the evening’s proceedings. Ashwani Kumar began the event by shedding light on the iconic play by Mohan Rakesh and introducing the performers for the evening with verses from Kalidas, celebrating clouds and rains in the city. He also thanked veteran actor, Saurabh Shukla and curator of Literature Live, Anil Dharkar for gracing the occasion. Mrs Sangita Jindal, chairperson of JSW foundation, extended a warm welcome and spoke passionately about JSW foundation’s association with Indian Novels Collective and the group’s translation project that aims to make Indian language classics accessible to English readers and popularise readings of classic Indian literature. She urged the audience to make the effort to broach Indian languages and keep the traditions and cultures flourishing, with adequate support. Dolly Thakore — well-known and respected senior theatre artiste and critic, began by paying tribute to Girish Karnad and spoke of her association with the playwright and her privilege of getting to work with him. Ram Gopal Bajaj, legend of Indian theatre and former director of National School of Drama, spoke of his fond memories of Karnad. He hailed him for his plays like ‘Tughlaq’ that made a mark of excellence in Indian theatre and literature. He then went on to speak of Mohan Rakesh’s ‘Ashaad Ka Ek Din’ and his experiences with the work.

Dolly Thakore — well-known and respected senior theatre artiste and critic, began by paying tribute to Girish Karnad and spoke of her association with the playwright and her privilege of getting to work with him. Ram Gopal Bajaj, legend of Indian theatre and former director of National School of Drama, spoke of his fond memories of Karnad. He hailed him for his plays like ‘Tughlaq’ that made a mark of excellence in Indian theatre and literature. He then went on to speak of Mohan Rakesh’s ‘Ashaad Ka Ek Din’ and his experiences with the work. The play reading began with Meeta Vasisht — versatile actress, director, producer and Priyanka Setia — another noted actress, playing the parts of Mallika and Ambika, respectively. The performers tried to give a sense of the Vachika Abhinaya(or spoken word) to the audience, which was beautifully conveyed through their camaraderie and expressive reading. The audience was also regaled with songs sung by Priyanka Setia at intervals, to match the theme and mood of the reading. Meeta Vasisht vivaciously contrasted the melancholic mood with a lively folk song, tirading her lover for leaving her. She spoke about the beauty of diverse folk traditions across India which have enriched art.

The play reading began with Meeta Vasisht — versatile actress, director, producer and Priyanka Setia — another noted actress, playing the parts of Mallika and Ambika, respectively. The performers tried to give a sense of the Vachika Abhinaya(or spoken word) to the audience, which was beautifully conveyed through their camaraderie and expressive reading. The audience was also regaled with songs sung by Priyanka Setia at intervals, to match the theme and mood of the reading. Meeta Vasisht vivaciously contrasted the melancholic mood with a lively folk song, tirading her lover for leaving her. She spoke about the beauty of diverse folk traditions across India which have enriched art. Ram Gopal Bajaj personified Kalidas with his mesmerizing performance. The fluidity of shifting characters was almost child’s play to this master performer. Meeta Vasisht also spoke about how she was moved to tears, the first time she read Malika’s monologue of ‘Ashaad Ka Ek Din’. The reading ended on a lighter note with her encouraging the audience to join in a song.

Ram Gopal Bajaj personified Kalidas with his mesmerizing performance. The fluidity of shifting characters was almost child’s play to this master performer. Meeta Vasisht also spoke about how she was moved to tears, the first time she read Malika’s monologue of ‘Ashaad Ka Ek Din’. The reading ended on a lighter note with her encouraging the audience to join in a song. We met in 1965, remember? In the MA English Literature class, taught by many luminaries, among whom the most brilliant were Nissim Ezekiel and Dr RB Patankar. You and Yasmeen Lukmani and I would traipse over to Dr Patankar’s room in the university building at Fort to hang around. That’s what it was. Hanging around, with cups of tea, and Dr Patankar sitting across the table, his fingertips together, and a characteristic half- smile lighting up his face. Often Dr MP Rege dropped in too, and our debates rose to some other level. How we argued. We were allowed to do that in those glorious days when ideas could be freely exchanged and challenged. You once said to me, “I wonder how you would look with your mouth shut.”

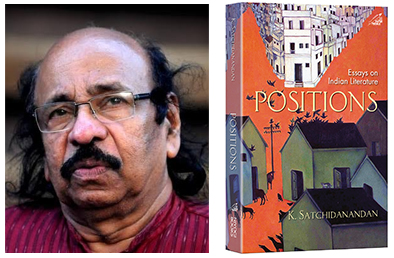

We met in 1965, remember? In the MA English Literature class, taught by many luminaries, among whom the most brilliant were Nissim Ezekiel and Dr RB Patankar. You and Yasmeen Lukmani and I would traipse over to Dr Patankar’s room in the university building at Fort to hang around. That’s what it was. Hanging around, with cups of tea, and Dr Patankar sitting across the table, his fingertips together, and a characteristic half- smile lighting up his face. Often Dr MP Rege dropped in too, and our debates rose to some other level. How we argued. We were allowed to do that in those glorious days when ideas could be freely exchanged and challenged. You once said to me, “I wonder how you would look with your mouth shut.” An eminent poet, critic, translator, playwright and travel-writer, K. Satchidanandan is often regarded as a torch-bearer of the socio-cultural revolution that redefined Malayalam literature. His first collection of poems, ‘Anchu Sooryan’ (Five Suns) came out in 1971 and since then he has published more than 20 collections of poetry. He has also authored an equal number of collections of essays on literature, philosophy and social issues, two plays, four books of travelogues and a memoir in Malayalam, besides four books on comparative Indian literature in English. He has won 51 awards including the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award and National Sahitya Akademi Award, Knighthood by the Govt of Italy, Dante Medal by Dante Institute, Ravenna, International Poetry for Peace Award by the government of UAE, and Indo-Polish Friendship Medal by the Govt of Poland.

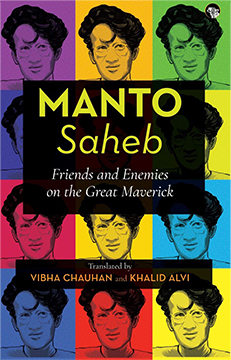

An eminent poet, critic, translator, playwright and travel-writer, K. Satchidanandan is often regarded as a torch-bearer of the socio-cultural revolution that redefined Malayalam literature. His first collection of poems, ‘Anchu Sooryan’ (Five Suns) came out in 1971 and since then he has published more than 20 collections of poetry. He has also authored an equal number of collections of essays on literature, philosophy and social issues, two plays, four books of travelogues and a memoir in Malayalam, besides four books on comparative Indian literature in English. He has won 51 awards including the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award and National Sahitya Akademi Award, Knighthood by the Govt of Italy, Dante Medal by Dante Institute, Ravenna, International Poetry for Peace Award by the government of UAE, and Indo-Polish Friendship Medal by the Govt of Poland. If asked to describe Saadat Hasan Manto in one word, this reviewer would unhesitatingly call him an enigma. Strange as it may seem, Manto, arguably the greatest short story writer in Urdu, failed in Urdu in his high school exams. What is no less surprising is that, incurable alcoholic that he was — he asked for whiskey while being driven in an ambulance to the hospital on his fatal journey and was obliged by his family members — he always wrote ‘786’, the numerical symbol of Bismillah ir Rahman nir Raheem, at the top of his writings, be they for broadcasting, publishing or films.

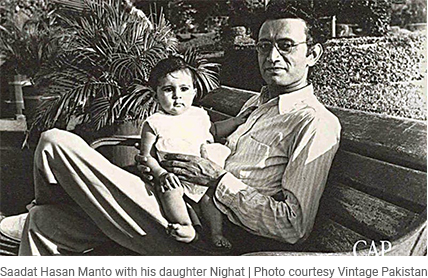

If asked to describe Saadat Hasan Manto in one word, this reviewer would unhesitatingly call him an enigma. Strange as it may seem, Manto, arguably the greatest short story writer in Urdu, failed in Urdu in his high school exams. What is no less surprising is that, incurable alcoholic that he was — he asked for whiskey while being driven in an ambulance to the hospital on his fatal journey and was obliged by his family members — he always wrote ‘786’, the numerical symbol of Bismillah ir Rahman nir Raheem, at the top of his writings, be they for broadcasting, publishing or films. The biggest tragedy in Manto’s life is recalled by his friend Krishan Chander, another well-known fiction writer. It was the death of his eldest child, a year and a half old son. Writes Chander: “The armour of cynicism that he had built up all around himself was smashed to smithereens.” According to Manto’s eldest daughter Nighat, the loss affected her father so much that he was transformed from a social drinker to an irreversible alcoholic.

The biggest tragedy in Manto’s life is recalled by his friend Krishan Chander, another well-known fiction writer. It was the death of his eldest child, a year and a half old son. Writes Chander: “The armour of cynicism that he had built up all around himself was smashed to smithereens.” According to Manto’s eldest daughter Nighat, the loss affected her father so much that he was transformed from a social drinker to an irreversible alcoholic. KTN Kottoor struck me at many different levels. His efficiency at judging political situations at a young age is something we can hope each one in the youth to have to save this country from doom. His poetic sense and his incredible clapback at stupid reviewers was such a spectacular scene to read. He laughs and says an incredible line which even today after a whole century is applicable at many levels, “….what they have read is not the poem. They have been reading the time and context of the poem. I am not a party to that.”

KTN Kottoor struck me at many different levels. His efficiency at judging political situations at a young age is something we can hope each one in the youth to have to save this country from doom. His poetic sense and his incredible clapback at stupid reviewers was such a spectacular scene to read. He laughs and says an incredible line which even today after a whole century is applicable at many levels, “….what they have read is not the poem. They have been reading the time and context of the poem. I am not a party to that.” The additional writeups are masterpieces in themselves. One is hit by a sense of conflict when reading it, is it the author speaking through the protagonist or is it the protagonist acting like th author? As one ponders over this fact and tries to unknot to the tight and complex knot, he is sucked into the short prose’s unimaginable beauty in language and it’s attachment to the realism and it’s sense of current timing. The poems etched to perfection, liked diamonds formed under pressure, present fractured and hidden within miles of paragraphs.

The additional writeups are masterpieces in themselves. One is hit by a sense of conflict when reading it, is it the author speaking through the protagonist or is it the protagonist acting like th author? As one ponders over this fact and tries to unknot to the tight and complex knot, he is sucked into the short prose’s unimaginable beauty in language and it’s attachment to the realism and it’s sense of current timing. The poems etched to perfection, liked diamonds formed under pressure, present fractured and hidden within miles of paragraphs. Rita Welinkar by Shanta Gokhale

Rita Welinkar by Shanta Gokhale Rishi Moolam by Jayakanthan

Rishi Moolam by Jayakanthan Swadesh Deepak by Maine Mandu Nahin Dekha

Swadesh Deepak by Maine Mandu Nahin Dekha Raat ka Reporter by Nirmal Verma

Raat ka Reporter by Nirmal Verma Herbert by Nabarun Bhattacharya

Herbert by Nabarun Bhattacharya Avinash by Shanta Gokhale

Avinash by Shanta Gokhale Brink by SL Bhyrappa

Brink by SL Bhyrappa

Qurratulain Hyder

Qurratulain Hyder Kamala Das

Kamala Das Mahasweta Devi

Mahasweta Devi Indira Goswami

Indira Goswami M K Indira

M K Indira Lalithambika Antharjanam

Lalithambika Antharjanam Bama

Bama Kundanika Kapadia

Kundanika Kapadia Krishna Sobti

Krishna Sobti Irawati Karve

Irawati Karve Amrita Pritam

Amrita Pritam Popati Hiranandani

Popati Hiranandani Yaddanapudi Sulochana Rani

Yaddanapudi Sulochana Rani Ismat Chughtai

Ismat Chughtai Basanta Kumari Patnaik

Basanta Kumari Patnaik