October 10, 2020

Sohini Banerjee & Mansi Dhanraj Shetty

Listicle

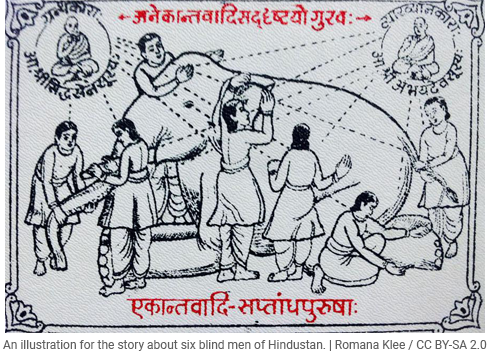

Explore mental health through these seven reads in Indian literature

The ongoing pandemic has wrought a debilitating impact on the collective mental health of the global community. According to a survey carried out among health professionals by The Bengaluru-based Suicide Prevention Foundation observed that nearly 65% therapists observed an increase in self-harm and suicide ideation or death wish amongst those who sought therapy, since the pandemic hit. This alarming statistic of soaring mental health cases, due to a combination of factors like forced isolation, fear of the virus, financial insecurity, domestic violence and rising anxiety, have further aggravated the unprecedented humanitarian crisis. Now more than ever, it is imperative that we fight the stigma and backlash around mental illness, which has long been a cultural taboo in the Indian social context, owing to widespread ignorance, misinformation and lack of health care resources. Literature, as a domain, ensures increased awareness about mental health issues and challenges the problematic stereotypes which relegate them to the closet. It accomplishes this by providing a peek into the many-shaded contradictions, ambiguities and vulnerabilities associated with mental health crises, facilitating catharsis, healing and emotional empowerment.

Indian literature’s nuanced exploration of mental health began much before it was integrated into our common vocabulary. Jayakanthan’s ‘Rishi Moolam’ and Shanta Gokhale’s ‘Rita Welinkar’ or ‘Avinash’ are striking examples of the same. This World Mental Health Day, we bring to you a diverse selection from the repository of Indian literary canon which reflect and address mental health. Although not an exhaustive list, these books enlighten us on how there is no one sanctioned way to engage with subterranean depths of the human mind.

Rita Welinkar by Shanta Gokhale

Rita Welinkar by Shanta Gokhale

Marathi

First Published 1990, translated into English by the writer herself in 1995

Outside, the palm trees wail, with the wild monsoon wind in their hair. In her hospital bed, Rita lies still, her eyes tuned to the wind. Recovering from her breakdown, she sifts through seasons full of memories—of her self-absorbed, critical parents; her demanding role as family breadwinner from the age of eighteen; her secret for an understanding of the events that brought her to the breaking-point. This well-structured novel helps readers understand what leads to Rita’s nervous breakdown and how important it is to recognise and address it as it is. Translated by Shanta Gokhale herself from the Marathi original, ‘Rita Welinkar’ won her much critical acclaim and the VS Khandekar Award from the Maharashtra government.

Rishi Moolam by Jayakanthan

Rishi Moolam by Jayakanthan

Tamil

First Published 1969

In his preface, Jayakanthan writes, ‘an individual devoid of a healthy orientation towards the man-woman relationship cannot be considered a properly developed person.’ In ‘Rishi Moolam’ Rajaraman, the protagonist, suffers from a psychosis about his sexuality. Not being able to forgive himself for thinking and acting in an unscrupulous way with his mother-like figure, the story captures his inner turmoil, self-denial and self-perception. The success of Jayakanthan lies in evoking in the reader a profound empathy with the tragically ‘deviant’ character who is a victim of a psychological malady arising from his suppressed libido and Oedpius complex rather than condemning him to moral policing.

Swadesh Deepak by Maine Mandu Nahin Dekha

Swadesh Deepak by Maine Mandu Nahin Dekha

Hindi

First Published in 2003

Swadesh Deepak, Hindi novelist, Sahitya Akademi winning playwright, short-story writer is remembered for his memoir ‘Maine Mandu Nahin Dekha’, an account of his seven-year battle with bipolar disorder. First serialised in the Hindi monthly, ‘Kathadesh’, the book accounts for shifts between time and space showing the reader the fragmented, collage-like quality of Deepak’s life as he dealt with his inner demons. The searing 331-page book is also being translated into English by Jerry Pinto.

Raat ka Reporter by Nirmal Verma

Raat ka Reporter by Nirmal Verma

Hindi

First published in 1989

Set during the Emergency (1975-77), Nirmal Verma’s ‘Raat ka Reporter’ addresses the theme of totalitarianism, oppression and violence that marked those 21 months. The protagonist Rishi is a journalist who gets warned about government surveillance and the possibility of his arrest at any time. By offering a lens into Rishi’s sudden realisation of impending custodial torture accompanied by his anxiety inducing self-reflexivity being targeted as the ‘enemy’ of the state—‘Raat ka Reporter’ lays bare the pervasive climate of state-manufactured paranoia through a psychological analysis of a fear-stricken chapter in Rishi’s life.

Herbert by Nabarun Bhattacharya

Herbert by Nabarun Bhattacharya

Bengali

First published in 1994

Set in a corner of old Calcutta in May 1992, when communism was collapsing all around, Nabarun Bhattacharya’s Sahitya Akademi winning novel ‘Herbert’ introduces us to the titular character Herbert Sarkar, sole proprietor of a company that delivers messages from the dead. The ‘scathingly satiric and yet deeply tender’ portrayal of a doomed young man through a mosaic of manic and immersive episodes, also holds a mirror to the city struggling to resist the same forces as him, that prove to be entirely beyond their control.

Avinash by Shanta Gokhale

Avinash by Shanta Gokhale

Marathi

First published in 1988

Unfolding at a relentless pace over a tight span of twenty-four hours, Shanta Gokhale’s Marathi play ‘Avinash’ is an intense family drama in which the tensions between various members of a middle-class family over the mental health of the eldest son escalates to a tragic climax. Talking about the text, Shanta Gokhale mentioned, ‘A character in my 1988 play ‘Avinash’ says the depression his older brother suffers from may not be the result entirely of some inborn psychological tic. Its roots might also lie in economics, in the social structure and the political system.’

Brink by SL Bhyrappa

Brink by SL Bhyrappa

Kannada

First Published in 1990

SL Bhyrappa’s epic Kannada novel ‘Anchu’ or ‘Brink’ portrays the sensitive relationship between Somasekhar—a widower and caregiver, and Amrita—an estranged woman with suicidal tendencies. An important and timely book — ‘Brink’ raises the question of mental health awareness by addressing depression from the point of view of the person suffering as well as the caregiver and meditates on the moral, philosophical and physical aspect of love between a man and a woman.

KTN Kottoor struck me at many different levels. His efficiency at judging political situations at a young age is something we can hope each one in the youth to have to save this country from doom. His poetic sense and his incredible clapback at stupid reviewers was such a spectacular scene to read. He laughs and says an incredible line which even today after a whole century is applicable at many levels, “….what they have read is not the poem. They have been reading the time and context of the poem. I am not a party to that.”

KTN Kottoor struck me at many different levels. His efficiency at judging political situations at a young age is something we can hope each one in the youth to have to save this country from doom. His poetic sense and his incredible clapback at stupid reviewers was such a spectacular scene to read. He laughs and says an incredible line which even today after a whole century is applicable at many levels, “….what they have read is not the poem. They have been reading the time and context of the poem. I am not a party to that.” The additional writeups are masterpieces in themselves. One is hit by a sense of conflict when reading it, is it the author speaking through the protagonist or is it the protagonist acting like th author? As one ponders over this fact and tries to unknot to the tight and complex knot, he is sucked into the short prose’s unimaginable beauty in language and it’s attachment to the realism and it’s sense of current timing. The poems etched to perfection, liked diamonds formed under pressure, present fractured and hidden within miles of paragraphs.

The additional writeups are masterpieces in themselves. One is hit by a sense of conflict when reading it, is it the author speaking through the protagonist or is it the protagonist acting like th author? As one ponders over this fact and tries to unknot to the tight and complex knot, he is sucked into the short prose’s unimaginable beauty in language and it’s attachment to the realism and it’s sense of current timing. The poems etched to perfection, liked diamonds formed under pressure, present fractured and hidden within miles of paragraphs.

The early 1900s saw the rise of Hindi children’s journals such as ‘Balak’, ‘Balsakha’ and ‘Kanya Manorajan’, which tried to instil nationalist morals.

The early 1900s saw the rise of Hindi children’s journals such as ‘Balak’, ‘Balsakha’ and ‘Kanya Manorajan’, which tried to instil nationalist morals. If asked to describe Saadat Hasan Manto in one word, this reviewer would unhesitatingly call him an enigma. Strange as it may seem, Manto, arguably the greatest short story writer in Urdu, failed in Urdu in his high school exams. What is no less surprising is that, incurable alcoholic that he was — he asked for whiskey while being driven in an ambulance to the hospital on his fatal journey and was obliged by his family members — he always wrote ‘786’, the numerical symbol of Bismillah ir Rahman nir Raheem, at the top of his writings, be they for broadcasting, publishing or films.

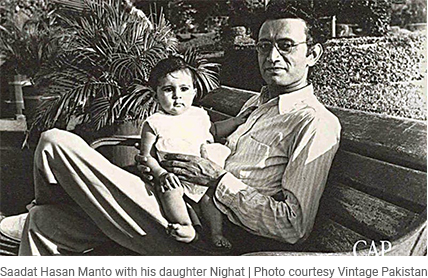

If asked to describe Saadat Hasan Manto in one word, this reviewer would unhesitatingly call him an enigma. Strange as it may seem, Manto, arguably the greatest short story writer in Urdu, failed in Urdu in his high school exams. What is no less surprising is that, incurable alcoholic that he was — he asked for whiskey while being driven in an ambulance to the hospital on his fatal journey and was obliged by his family members — he always wrote ‘786’, the numerical symbol of Bismillah ir Rahman nir Raheem, at the top of his writings, be they for broadcasting, publishing or films. The biggest tragedy in Manto’s life is recalled by his friend Krishan Chander, another well-known fiction writer. It was the death of his eldest child, a year and a half old son. Writes Chander: “The armour of cynicism that he had built up all around himself was smashed to smithereens.” According to Manto’s eldest daughter Nighat, the loss affected her father so much that he was transformed from a social drinker to an irreversible alcoholic.

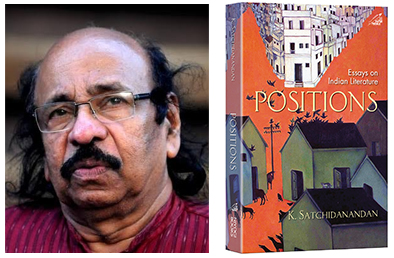

The biggest tragedy in Manto’s life is recalled by his friend Krishan Chander, another well-known fiction writer. It was the death of his eldest child, a year and a half old son. Writes Chander: “The armour of cynicism that he had built up all around himself was smashed to smithereens.” According to Manto’s eldest daughter Nighat, the loss affected her father so much that he was transformed from a social drinker to an irreversible alcoholic. An eminent poet, critic, translator, playwright and travel-writer, K. Satchidanandan is often regarded as a torch-bearer of the socio-cultural revolution that redefined Malayalam literature. His first collection of poems, ‘Anchu Sooryan’ (Five Suns) came out in 1971 and since then he has published more than 20 collections of poetry. He has also authored an equal number of collections of essays on literature, philosophy and social issues, two plays, four books of travelogues and a memoir in Malayalam, besides four books on comparative Indian literature in English. He has won 51 awards including the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award and National Sahitya Akademi Award, Knighthood by the Govt of Italy, Dante Medal by Dante Institute, Ravenna, International Poetry for Peace Award by the government of UAE, and Indo-Polish Friendship Medal by the Govt of Poland.

An eminent poet, critic, translator, playwright and travel-writer, K. Satchidanandan is often regarded as a torch-bearer of the socio-cultural revolution that redefined Malayalam literature. His first collection of poems, ‘Anchu Sooryan’ (Five Suns) came out in 1971 and since then he has published more than 20 collections of poetry. He has also authored an equal number of collections of essays on literature, philosophy and social issues, two plays, four books of travelogues and a memoir in Malayalam, besides four books on comparative Indian literature in English. He has won 51 awards including the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award and National Sahitya Akademi Award, Knighthood by the Govt of Italy, Dante Medal by Dante Institute, Ravenna, International Poetry for Peace Award by the government of UAE, and Indo-Polish Friendship Medal by the Govt of Poland. We met in 1965, remember? In the MA English Literature class, taught by many luminaries, among whom the most brilliant were Nissim Ezekiel and Dr RB Patankar. You and Yasmeen Lukmani and I would traipse over to Dr Patankar’s room in the university building at Fort to hang around. That’s what it was. Hanging around, with cups of tea, and Dr Patankar sitting across the table, his fingertips together, and a characteristic half- smile lighting up his face. Often Dr MP Rege dropped in too, and our debates rose to some other level. How we argued. We were allowed to do that in those glorious days when ideas could be freely exchanged and challenged. You once said to me, “I wonder how you would look with your mouth shut.”

We met in 1965, remember? In the MA English Literature class, taught by many luminaries, among whom the most brilliant were Nissim Ezekiel and Dr RB Patankar. You and Yasmeen Lukmani and I would traipse over to Dr Patankar’s room in the university building at Fort to hang around. That’s what it was. Hanging around, with cups of tea, and Dr Patankar sitting across the table, his fingertips together, and a characteristic half- smile lighting up his face. Often Dr MP Rege dropped in too, and our debates rose to some other level. How we argued. We were allowed to do that in those glorious days when ideas could be freely exchanged and challenged. You once said to me, “I wonder how you would look with your mouth shut.” What is the Gulf dream?

What is the Gulf dream?