Translation: A cultural transfer

After tens of thousands of years of evolution through which language was fundamental for the development of mankind, we have reached the age of globalization. Though, today, there are few borders left that have not been breached by the internet, electronic mail and telecommunication, language may still be a barrier in communication and translation is necessary for successful communication.

After tens of thousands of years of evolution through which language was fundamental for the development of mankind, we have reached the age of globalization. Though, today, there are few borders left that have not been breached by the internet, electronic mail and telecommunication, language may still be a barrier in communication and translation is necessary for successful communication.

A language postulates in itself a model of reality and a phonic association with the universe it describes, so we cannot separate language from culture. Both linguistic equivalence and cultural transfer are at stake when translating. Translation is a cultural fact that means necessarily cross-cultural exchange and understanding.

The translator’s purpose is not just to translate a printed literary text into another language but to be the mediator who could initiate and even induce the reader to internalize the representative text of an alien culture.

I remember A K Ramanujan, who while translating U R Ananthamurthy’s Novel Samskara opined, “A translator hopes not only to translate a text but hopes to translate a non-native reader into a native one. This statement of Ramanujan’s “to translate a non-native reader into a native one” very simply but powerfully introduces the crucial notion of cultural translation. So, through translations of creative writing, cultural bridges of understanding are securely constructed.

Early Translations

In the early centuries of Christian era, Buddhist texts were translated into Chinese and later into Tibetan. In the 11th century, Sanskrit texts began to be translated into Assamese, Kannada, Marathi, Telugu etc. At the same time translation began to be done in the Persian language too.

Zain ul Abidin (1420 -1470), the ruler of Kashmir, established a bureau for bilateral renderings between Sanskrit and Persian. Dara Shikoh’s Persian translations of the Upanishads and Mulla Ahmed Kashmiri’s rendition of Mahabharata are among the major landmarks along this stream.

In the 17th -18th century, the great Sikh guru, Guru Gobind Singh set up a bureau and had a large number of Sanskrit texts translated into Punjabi.

In 18th century, major universities in Europe had chairs in Sanskrit and Sanskrit studies had come to enjoy immense prestige. As the century progressed, Sanskrit studies immensely shaped the European mind. All the major European minds of the 19th century were either Sanskritists or by their own admission had been deeply involved in Indian thought –Humboldt, Fichte, Hegel, Goethe, Schopenhauer, Kant, Nietzsche, Schelling, Ferdinand de Saussure, Roman Jakobson.

Translations in the British period

The British phase of translation into English culminated in William Jone’s translation of Kalidasa’s Abhigyana Shakuntalam.

The late nineteen eighties and nineties was an exciting period for the discipline of translation studies in India. Seminal writings like G N Devy, In Another Tongue: Essays on Indian English Literature (1993), Sujit Mukherjees’s Translation as Discovery and Other Essays on Indian Literature in English Translation (1994), Tejaswani Niranjana, Siting Translation: History, Post Strucuralism and the Colonial Context (1995), and many anthologies like Pramod Talgeri and Verman S.B (Editors) Literature in Translation from Cultural Transference to Metonymic Displacement (1988), A K Singh Edited, Translation: Its theory and Practice (1996), Dingwaney, Anuradha and Carol Maier (Editors) Between Language and Cultures: Translations and Cross Cultural Texts (1996), Tutun Mukherjee (Edited)Translation : From Periphery to Centre Stage (1998) and Susan Bassnett and Trivedi (Editors) Post Colonial Translation: Theory and Practice (1999) burst into the scene.

Translation of Malayalam works in English

The very foundation of Indian Literature is based on translations. India is a multilingual country. According to scholar G N Devy there are 780 languages spoken in India.

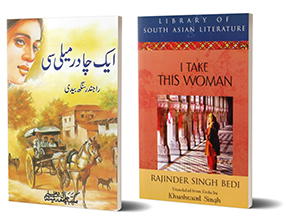

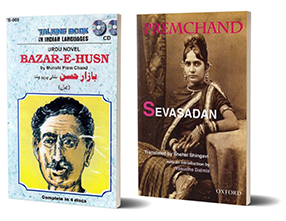

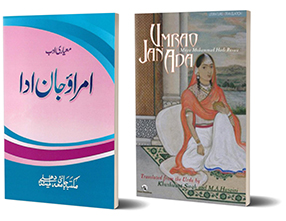

Translation builds bridges and opens the door for those who would not otherwise have access to the original and thereby unite different cultures. The literary works of different Indian languages especially Bengali literature were translated into Malayalam during the early seventies. Premchand, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Paulo Coelho and Mario Vargas Llosa have come into Malayalam via English translations and found great readership.

Translation has been gaining ground as an important discipline in literary field and has been growing rapidly in the multicultural world. Translation is an important tool to disseminate regional literatures, to make them go beyond the territories of their native domain and reach global readership. Translation is a creative process which involves two languages. It involves critical thinking and evaluation. Translation should be as far as possible close to the original in language, style and content.

Be it the case of Indian languages or foreign languages, the cultural elements are in danger, while translations are done. Given the fact that Malayalam language is culturally rich with its traditional customs, beliefs and practices, translation of literary works from Malayalam to English becomes a challenge for the translator, as I mentioned above, the translator has to bring a non-native reader into a native one.

Words like pooram, padayani, koithu pattu, palliyodam, kanji, appam etc…reflect the cultural aspects of Keralites which may not necessarily be found in the target language into which the source text is translated, especially in English. Hence translation is not a mere linguistic substitution, it’s a cultural transfer. The translator has to facilitate the message, meaning and cultural elements from one language to another and create an equivalent response from the receivers.

When one talks of Malayalam works in English the titles that comes to mind quickly are Basheer’s Ente Uppupakoru Ana Undayirunnu, Thakazhi’s Chemmeen, S K Pottekkat’s Oru Deshathinte Katha and M T’s Randamoozham.

Of late, there has been an increase in translation of Malayalam fiction into English. Benyamin’s Aadu Jeevitham was translated as Goat Days by Joseph Koyipally and Subhash Chandran’s Manushyanu Oru Aamukham translated as Preface to Man by Fathima E V, K R Meera’s Aarachaar translated as Hangwoman by J Devika, T D Ramakrishnan’s Sugandhi Alias Andal Devanayaki and Francis Itty Kora translated with the same names by Priya K Nair, Othapu by Sara Joseph translated as Othappuby Valson Thampu have made Malayalam fiction more visible internationally.

Of late, there has been an increase in translation of Malayalam fiction into English. Benyamin’s Aadu Jeevitham was translated as Goat Days by Joseph Koyipally and Subhash Chandran’s Manushyanu Oru Aamukham translated as Preface to Man by Fathima E V, K R Meera’s Aarachaar translated as Hangwoman by J Devika, T D Ramakrishnan’s Sugandhi Alias Andal Devanayaki and Francis Itty Kora translated with the same names by Priya K Nair, Othapu by Sara Joseph translated as Othappuby Valson Thampu have made Malayalam fiction more visible internationally.

The Indian literary scene has witnessed a great change as far as translation is considered in the last decade. Crossword awards have changed the translation scenario in India. Beginning with fiction and then adding on translation awards in its scheme of things have resulted in more and more Indian language fiction being translated into English.

It’s noteworthy that Malayalam fiction has made its presence over the years. The list also includes among others, On the banks of Mayyazhi by M Mukundan- translated by Gita Krishnankutty, Kesavan’s Lamentations translated by Gita Krishnankutty, P Sachidanandan’ Govardhan’s travels translated by Gita Krishnankutty, Narayan’s Kocharethi: The Araya Woman translated by Catherine Thankamma, and Benyamin’s Jasmine Days translated by Shahnaz Habib

The Juggernaut published Swarga, the English translation of Enmakaje by Ambikasuthan Mangad. Translated by J Devika, it qualifies to be a miserable exercise. I am citing an example here: in the Malayalam original, the sentence reads “Vanaprasthan mare pole kaatil kazhiyunna namukku ee kurish ottum cherukayilla.” (Pg 18)

The Juggernaut published Swarga, the English translation of Enmakaje by Ambikasuthan Mangad. Translated by J Devika, it qualifies to be a miserable exercise. I am citing an example here: in the Malayalam original, the sentence reads “Vanaprasthan mare pole kaatil kazhiyunna namukku ee kurish ottum cherukayilla.” (Pg 18)

The English translation reads: “This cross doesn’t suit us who live in the forest, who seek a life of contemplation in the wilderness.” The author meant that the child is a burden to them who are living in the wilderness. Devika’s translation “this cross doesn’t suit us” is way off the mark. Likewise, other errors have crept in. The end result is that, the Malayalam novel which has 18 reprints so far, while being introduced into English, got lost in translation.

A translator can enhance the original work or mess it up.

Everyone familiar with translation, theory and practice is aware that translation no longer entails linguistic substitution or mere code– switching, but is regarded as a “cultural transfer.”

Linguist Eugene Nida states that the role of the translator is to facilitate the transfer of message, meaning and cultural elements from one language to another and to create an equivalent response from the receivers i.e. the primary responsibility of the translators is to recreate in the target language the reader responses that the text in the source language had created. The ideal translation should therefore be accurate, natural and communicative.

All said and done, translation is an attempt to introduce a literary work from one language to another. We have had access to world literature and Indian Literature because of translations.

A gifted translator is a creator. He can remain close to the text and then render it creatively and bring the source language alive in the target language. Translation is a creative approximation of the original. The original and the translation must play in harmony, like jugalbandi. It’s here that translation becomes an art.

Santhosh Alex

Santhosh Alex

Dr Santosh Alex is a Poet, Translator and Poetry Curator. He is the author of 35 books including poetry, criticism and translations.

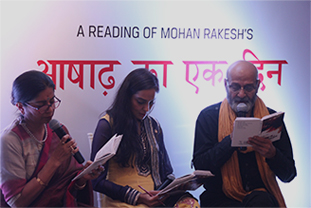

The Monsoon Reading of ‘Ashaad Ka Ek Din’ —the first modern Hindi play by Mohan Rakesh held at Jindal Mansion on Friday, July, 5, 2019 was attended by a motley group of theatre lovers and some renowned artistes. Sangita Jindal, Amrita Somaiya, Ashwani Kumar, Anuradha Parikh — the core group members of Indian Novels Collective, were all present to support and conduct the evening’s proceedings. Ashwani Kumar began the event by shedding light on the iconic play by Mohan Rakesh and introducing the performers for the evening with verses from Kalidas, celebrating clouds and rains in the city. He also thanked veteran actor, Saurabh Shukla and curator of Literature Live, Anil Dharkar for gracing the occasion. Mrs Sangita Jindal, chairperson of JSW foundation, extended a warm welcome and spoke passionately about JSW foundation’s association with Indian Novels Collective and the group’s translation project that aims to make Indian language classics accessible to English readers and popularise readings of classic Indian literature. She urged the audience to make the effort to broach Indian languages and keep the traditions and cultures flourishing, with adequate support.

The Monsoon Reading of ‘Ashaad Ka Ek Din’ —the first modern Hindi play by Mohan Rakesh held at Jindal Mansion on Friday, July, 5, 2019 was attended by a motley group of theatre lovers and some renowned artistes. Sangita Jindal, Amrita Somaiya, Ashwani Kumar, Anuradha Parikh — the core group members of Indian Novels Collective, were all present to support and conduct the evening’s proceedings. Ashwani Kumar began the event by shedding light on the iconic play by Mohan Rakesh and introducing the performers for the evening with verses from Kalidas, celebrating clouds and rains in the city. He also thanked veteran actor, Saurabh Shukla and curator of Literature Live, Anil Dharkar for gracing the occasion. Mrs Sangita Jindal, chairperson of JSW foundation, extended a warm welcome and spoke passionately about JSW foundation’s association with Indian Novels Collective and the group’s translation project that aims to make Indian language classics accessible to English readers and popularise readings of classic Indian literature. She urged the audience to make the effort to broach Indian languages and keep the traditions and cultures flourishing, with adequate support. Dolly Thakore — well-known and respected senior theatre artiste and critic, began by paying tribute to Girish Karnad and spoke of her association with the playwright and her privilege of getting to work with him. Ram Gopal Bajaj, legend of Indian theatre and former director of National School of Drama, spoke of his fond memories of Karnad. He hailed him for his plays like ‘Tughlaq’ that made a mark of excellence in Indian theatre and literature. He then went on to speak of Mohan Rakesh’s ‘Ashaad Ka Ek Din’ and his experiences with the work.

Dolly Thakore — well-known and respected senior theatre artiste and critic, began by paying tribute to Girish Karnad and spoke of her association with the playwright and her privilege of getting to work with him. Ram Gopal Bajaj, legend of Indian theatre and former director of National School of Drama, spoke of his fond memories of Karnad. He hailed him for his plays like ‘Tughlaq’ that made a mark of excellence in Indian theatre and literature. He then went on to speak of Mohan Rakesh’s ‘Ashaad Ka Ek Din’ and his experiences with the work. The play reading began with Meeta Vasisht — versatile actress, director, producer and Priyanka Setia — another noted actress, playing the parts of Mallika and Ambika, respectively. The performers tried to give a sense of the Vachika Abhinaya(or spoken word) to the audience, which was beautifully conveyed through their camaraderie and expressive reading. The audience was also regaled with songs sung by Priyanka Setia at intervals, to match the theme and mood of the reading. Meeta Vasisht vivaciously contrasted the melancholic mood with a lively folk song, tirading her lover for leaving her. She spoke about the beauty of diverse folk traditions across India which have enriched art.

The play reading began with Meeta Vasisht — versatile actress, director, producer and Priyanka Setia — another noted actress, playing the parts of Mallika and Ambika, respectively. The performers tried to give a sense of the Vachika Abhinaya(or spoken word) to the audience, which was beautifully conveyed through their camaraderie and expressive reading. The audience was also regaled with songs sung by Priyanka Setia at intervals, to match the theme and mood of the reading. Meeta Vasisht vivaciously contrasted the melancholic mood with a lively folk song, tirading her lover for leaving her. She spoke about the beauty of diverse folk traditions across India which have enriched art. Ram Gopal Bajaj personified Kalidas with his mesmerizing performance. The fluidity of shifting characters was almost child’s play to this master performer. Meeta Vasisht also spoke about how she was moved to tears, the first time she read Malika’s monologue of ‘Ashaad Ka Ek Din’. The reading ended on a lighter note with her encouraging the audience to join in a song.

Ram Gopal Bajaj personified Kalidas with his mesmerizing performance. The fluidity of shifting characters was almost child’s play to this master performer. Meeta Vasisht also spoke about how she was moved to tears, the first time she read Malika’s monologue of ‘Ashaad Ka Ek Din’. The reading ended on a lighter note with her encouraging the audience to join in a song. Mirat-al-Urus by Nazir Ahmad

Mirat-al-Urus by Nazir Ahmad

After tens of thousands of years of evolution through which language was fundamental for the development of mankind, we have reached the age of globalization. Though, today, there are few borders left that have not been breached by the internet, electronic mail and telecommunication, language may still be a barrier in communication and translation is necessary for successful communication.

After tens of thousands of years of evolution through which language was fundamental for the development of mankind, we have reached the age of globalization. Though, today, there are few borders left that have not been breached by the internet, electronic mail and telecommunication, language may still be a barrier in communication and translation is necessary for successful communication. Of late, there has been an increase in translation of Malayalam fiction into English. Benyamin’s Aadu Jeevitham was translated as Goat Days by Joseph Koyipally and Subhash Chandran’s Manushyanu Oru Aamukham translated as Preface to Man by Fathima E V, K R Meera’s Aarachaar translated as Hangwoman by J Devika, T D Ramakrishnan’s Sugandhi Alias Andal Devanayaki and Francis Itty Kora translated with the same names by Priya K Nair, Othapu by Sara Joseph translated as Othappuby Valson Thampu have made Malayalam fiction more visible internationally.

Of late, there has been an increase in translation of Malayalam fiction into English. Benyamin’s Aadu Jeevitham was translated as Goat Days by Joseph Koyipally and Subhash Chandran’s Manushyanu Oru Aamukham translated as Preface to Man by Fathima E V, K R Meera’s Aarachaar translated as Hangwoman by J Devika, T D Ramakrishnan’s Sugandhi Alias Andal Devanayaki and Francis Itty Kora translated with the same names by Priya K Nair, Othapu by Sara Joseph translated as Othappuby Valson Thampu have made Malayalam fiction more visible internationally. The Juggernaut published Swarga, the English translation of Enmakaje by Ambikasuthan Mangad. Translated by J Devika, it qualifies to be a miserable exercise. I am citing an example here: in the Malayalam original, the sentence reads “Vanaprasthan mare pole kaatil kazhiyunna namukku ee kurish ottum cherukayilla.” (Pg 18)

The Juggernaut published Swarga, the English translation of Enmakaje by Ambikasuthan Mangad. Translated by J Devika, it qualifies to be a miserable exercise. I am citing an example here: in the Malayalam original, the sentence reads “Vanaprasthan mare pole kaatil kazhiyunna namukku ee kurish ottum cherukayilla.” (Pg 18) Santhosh Alex

Santhosh Alex “He finally managed to scrape through with a third division – and you would be truly bowled over by the fact that he failed his Urdu exam!

“He finally managed to scrape through with a third division – and you would be truly bowled over by the fact that he failed his Urdu exam! The historian Ayesha Jalal, (who is Manto’s grand-niece) wrote in her book about him, The Pity of Partition: “Whether he was writing about prostitutes, pimps or criminals, Manto wanted to impress upon his readers that these disreputable people were also human, much more than those who cloaked their failings in a thick veil of hypocrisy.”

The historian Ayesha Jalal, (who is Manto’s grand-niece) wrote in her book about him, The Pity of Partition: “Whether he was writing about prostitutes, pimps or criminals, Manto wanted to impress upon his readers that these disreputable people were also human, much more than those who cloaked their failings in a thick veil of hypocrisy.”

“Manto’s stories were radical in their own time and they are still radical,” says the author and academic Preti Taneja. “Manto does not shy away from the idea that women have sexual needs and their own sexual vision that has nothing to do with being in love with someone else.” “Manto is as skilled as the best short story writers of the Russian and western tradition” says Taneja ‘and it is very sad that he has been erased from the literary canon.”

“Manto’s stories were radical in their own time and they are still radical,” says the author and academic Preti Taneja. “Manto does not shy away from the idea that women have sexual needs and their own sexual vision that has nothing to do with being in love with someone else.” “Manto is as skilled as the best short story writers of the Russian and western tradition” says Taneja ‘and it is very sad that he has been erased from the literary canon.” “When I was at high school, he wasn’t part of our syllabus,” recalls Pakistani writer Mohammed Hanif, whose work shares the black humour and political bite of Manto. “The people who read his books were considered rebels; edgy people who didn’t conform. Reading Manto made you realise that literature did not always have to conform. It does not always have to tell polite stories. It also gave me the idea that you can write about stuff that is happening right now. Somehow, we believed that something that happened in the past is the subject of fiction whereas what is happening now is the subject of news or commentary.”

“When I was at high school, he wasn’t part of our syllabus,” recalls Pakistani writer Mohammed Hanif, whose work shares the black humour and political bite of Manto. “The people who read his books were considered rebels; edgy people who didn’t conform. Reading Manto made you realise that literature did not always have to conform. It does not always have to tell polite stories. It also gave me the idea that you can write about stuff that is happening right now. Somehow, we believed that something that happened in the past is the subject of fiction whereas what is happening now is the subject of news or commentary.” Salman Rushdie, author of Midnight’s Children, describes him as “unparalleled in his generation”. “There are few writers,” says Rushdie, “who straddle both India and Pakistan as he does, and who engage with the deepest problems of both countries.” According to Rushdie, Bombay was always Manto’s “greatest inspiration”.

Salman Rushdie, author of Midnight’s Children, describes him as “unparalleled in his generation”. “There are few writers,” says Rushdie, “who straddle both India and Pakistan as he does, and who engage with the deepest problems of both countries.” According to Rushdie, Bombay was always Manto’s “greatest inspiration”. “He has been celebrated in academia and the arts circle but on a national level there has been if not a shame then a discomfort,” says the actor and film-maker Sarmad Khoosat who directed and starred in the recent Pakistani biopic on Manto.

“He has been celebrated in academia and the arts circle but on a national level there has been if not a shame then a discomfort,” says the actor and film-maker Sarmad Khoosat who directed and starred in the recent Pakistani biopic on Manto. Last year, actor and filmmaker Nandita Das released a biopic on Manto. When asked why she chose Manto as her subject, she mentioned, “What drew me to the writer was his free spirit and courage to stand up against orthodoxy of all kinds. He wrote with a rare sensitivity and empathy for his characters.”

Last year, actor and filmmaker Nandita Das released a biopic on Manto. When asked why she chose Manto as her subject, she mentioned, “What drew me to the writer was his free spirit and courage to stand up against orthodoxy of all kinds. He wrote with a rare sensitivity and empathy for his characters.” Theatre activist and playwright Shahid Anwar, whose play Ghair Zaroori Log (persona non-grata) was based on six of Manto’s stories, said during an interaction with The Hindu in 2014: “The principal problem with Manto’s literary work was that somehow he got confined to the Partition and its framework.” No wonder that most of the stories that Anwar chose for his play, including ‘Hatak’, ‘Pairan’ and ‘Mummy’, are those that often go unnoticed in Manto’s body of work.

Theatre activist and playwright Shahid Anwar, whose play Ghair Zaroori Log (persona non-grata) was based on six of Manto’s stories, said during an interaction with The Hindu in 2014: “The principal problem with Manto’s literary work was that somehow he got confined to the Partition and its framework.” No wonder that most of the stories that Anwar chose for his play, including ‘Hatak’, ‘Pairan’ and ‘Mummy’, are those that often go unnoticed in Manto’s body of work. “Manto remains unsung for the craft of storytelling, which was impeccable. His craft, the form of his short story is noted for its brevity at a time when Urdu writers exaggerated every word and more words were considered almost like fine art,” mentioned Javed Akhtar, poet, scriptwriter and a member of the Progressive Movement, in a conversation about Manto on his birth centenary.

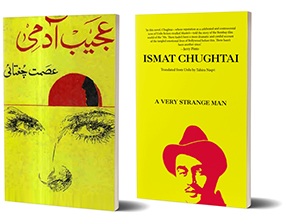

“Manto remains unsung for the craft of storytelling, which was impeccable. His craft, the form of his short story is noted for its brevity at a time when Urdu writers exaggerated every word and more words were considered almost like fine art,” mentioned Javed Akhtar, poet, scriptwriter and a member of the Progressive Movement, in a conversation about Manto on his birth centenary. However, no piece on Manto is complete without Ismat Chugtai’s opinion about him. After Manto’s death, Chughtai wrote a letter to the people of Pakistan where she questioned the regime’s decision to honour the artist whom they had tortured and slapped with sedition and obscenity charges when he was living. She said:

However, no piece on Manto is complete without Ismat Chugtai’s opinion about him. After Manto’s death, Chughtai wrote a letter to the people of Pakistan where she questioned the regime’s decision to honour the artist whom they had tortured and slapped with sedition and obscenity charges when he was living. She said: “Where the mind is without fear

“Where the mind is without fear

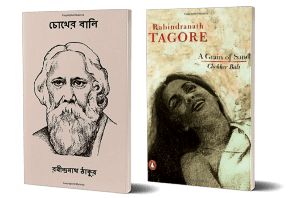

GORA (1909)

GORA (1909)

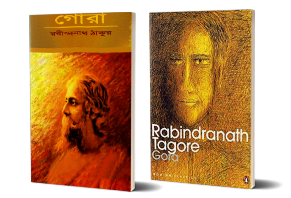

SHESHER KABITA (1929)

SHESHER KABITA (1929) Pather Panchali by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay

Pather Panchali by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay

Last Friday evening (February 8, 2019), The David Sassoon Library Grounds witnessed a houseful celebration of literature, captivating the young and old, alike. First on stage was Ashwani Kumar, co-founder of Indian Novels Collective, addressing the gathering. He introduced the Novels to the audience and highlighted the need to experiment with genres to popularise Indian classics.

Last Friday evening (February 8, 2019), The David Sassoon Library Grounds witnessed a houseful celebration of literature, captivating the young and old, alike. First on stage was Ashwani Kumar, co-founder of Indian Novels Collective, addressing the gathering. He introduced the Novels to the audience and highlighted the need to experiment with genres to popularise Indian classics. Priyanka Setia — theatre artiste and Bollywood actress, has been a part of the Indian Novels Collective family. Talking about this unique association with Vidya Shah, Priyanka Setia commented, “Vidya is so loving, so giving. It never felt like I was collaborating with her for the first time; it was very comfortable to work with her. Performing with Vidya was a beautiful experience!”

Priyanka Setia — theatre artiste and Bollywood actress, has been a part of the Indian Novels Collective family. Talking about this unique association with Vidya Shah, Priyanka Setia commented, “Vidya is so loving, so giving. It never felt like I was collaborating with her for the first time; it was very comfortable to work with her. Performing with Vidya was a beautiful experience!” Priyanka Setia enticed the audience with the characters’ unapologetic sexuality. On the one hand, Mitro unabashedly expresses her sexual desires while Mauzo’s Karmelin uses her sensuality in a calculative and controlled manner. The excerpts read from the Novels helped the audience capture the essence of the characters. Vidya Shah corresponded to these characters with some beautiful Ghazals from Janki Bai’s Raseeli Tori Akheeya and Begum Akhtar’s Humari Atariya Pe followed by Humko Mita Sake for Karmelin.

Priyanka Setia enticed the audience with the characters’ unapologetic sexuality. On the one hand, Mitro unabashedly expresses her sexual desires while Mauzo’s Karmelin uses her sensuality in a calculative and controlled manner. The excerpts read from the Novels helped the audience capture the essence of the characters. Vidya Shah corresponded to these characters with some beautiful Ghazals from Janki Bai’s Raseeli Tori Akheeya and Begum Akhtar’s Humari Atariya Pe followed by Humko Mita Sake for Karmelin.

The readings by Priyanka Setia left the audience wanting more as she teased them by withholding the end. Vidya Shah’s mesmerising voice with a varied selection of songs blended with the women characters being read effortlessly, adding charm to the classic Indian writings and experiencing Mitro, Karmelin and Sudha — the three women from Indian literature in an entrancing way. The characters indeed, came alive and left their imprints on the minds.

The readings by Priyanka Setia left the audience wanting more as she teased them by withholding the end. Vidya Shah’s mesmerising voice with a varied selection of songs blended with the women characters being read effortlessly, adding charm to the classic Indian writings and experiencing Mitro, Karmelin and Sudha — the three women from Indian literature in an entrancing way. The characters indeed, came alive and left their imprints on the minds.